Until recently, the American novelist Barbara Kingsolver was best known to me for an article she wrote in Utne magazine, something to do with the virtues of off-grid, off-the-paved-and-beaten-track, off-beat living. Translation? Going rural. Growing your own. A willing ignorance of haste and celebrity and media and the quest for higher consumption. This is how I remember the piece, and it was a thoughtful and eloquent one. I was well aware, though, that this was the Poisonwood Bible woman, she of the large sales figures and the Oprah stamp of literary approval. This may account, along with my own embrace of slow literary living, for how long it took me to get around to the Bible. I should’ve gotten there faster.

It’s a remarkable book, hugely ambitious and earnest and uneven. I found it thrilling and irritating, filled with gorgeous and poetic phrasing (especially in the interior monologues) alongside sometimes clangingly explanatory and unlikely dialogue, with characters both beautifully and cartoonishly drawn. It follows a Georgia missionary family, the Prices, that goes to the Congo in 1960, where it experiences brutal hardship of its own (mainly of its patriarch’s) making, but also that of the Congolese in general as they go from Belgian colony to “independence” under the brutal Mbutu regime. We follow the lives of the Price women, a mother and four daughters, and their mainly male-made problems. The rich characters are the women.

Men do not come off terribly well in The Poisonwood Bible, which when it errs does so on the side of the Nobly Suffering Woman archetype. (It also portrays the dignity of women under hardship in a heart-wrenching way, don’t mistake me.) The ultra-zealous preacher Nathan Price is a bully and a bad advertisement for Christianity, an extremist and even a sadist in his manic, ignorant spreading of a patronizing Word. He never quite feels real, though there are some belated attempts to explain the creation of this monster. (There is no attempt to explain the other bastards at all.) Meanwhile, the two benevolent male characters are upholders of a stainless, if eccentric, goodness. They never quite seem real, either, though they are sometimes interesting.

Reverend Price’s deeply oppressed wife, Orleanna, is a poetic voice of bitter hindsight, and the voices of two of her daughters are the narrative highs and lows of the book. The mute and brilliant Adah is a fascinating creation with strange, gripping perspectives on the occasionally comic but relentlessly painful events of the book. The lovely and skin-deep eldest daughter, Rachel, is the counterbalance to the female heroism mentioned above. She became increasingly annoying to me as the book went on, so unrelentingly vain and self-absorbed was she. My vain imagining is that Kingsolver just had too much fun skewering the vacuous cheerleader belles of her own high school days. (The malapropisms were amusing at first, but Rachel’s verbal mistakes get wearisome. Her comments about language students working on their French “congregations”, well, okay, but when she complains about someone not having the simple “confederation” to get drinks for everyone in the room? I’ve now forgotten the most irritating examples; suffice to say that they begin to smack of Kingsolver trying way too hard, or having too much fun, or not knowing when enough was enough. Let’s blame the editor.)

About midway through this 650-page saga, the bloom came off what had been a terribly thorny but breathtaking rose. There were too many points to be made, too many clumsy character assassinations, social criticisms and historical observations that burst out of their literary clothing and lay there naked on the page. I was actually angry, at a certain point, because so much of the book had been so movingly, compellingly done up to that point. The story just went on too long, tried to do too much. But once I relaxed enough to accept what Kingsolver had in mind, I was able to enjoy the weaker back end of the book, though not quite with the wonder and alarm of the first half. Okay, she’s indicting the entire enterprise of African exploitation, American ignorance and materialism, male weakness and chauvinism. Let’s go with that. So I did, and I learned lots of history and context and continued to find narrative brilliance in some of the several narrators. The conclusion moved me again, and I felt content with the ending.

And a funny thing. (This reviewing of literature, I must say, is a strange and troublesome effort. I’m being forcibly reminded of what the producers of Brick, a literary magazine, place in the front of each edition, a quote from Rilke: “Works of art are of an infinite loneliness and with nothing to be so little appreciated as with criticism. Only love can grasp and hold and fairly judge them.” There is a wonderful lot to love in The Poisonwood Bible. That sounds lame now. Well, and there’s this, too, which should undermine some of what I wrote above: Barbara Kingsolver is a fountain of good writing, and even with respect to novels, only part of her mighty flow, the score is BK 5, JH 0. So there.) So reading, thinking about books we read and remark on: you know what? Aside from its frequently stunning portrait of the colonial project, I may remember this novel most for something that precedes it. In Kingsolver’s introductory remarks, she ends in gratitude to Steven (her husband?) for his belief that “a spirit of adventure will usually suffice…” I love the brevity and punch of that line. Of course, it most spectacularly did not suffice in the individual mission of the crazed Nathan Price, nor of the European and American mission to get from Africa what they wanted. But for this pale adventurer, the words are branded on my brain. They’re beside my writing desk, too.

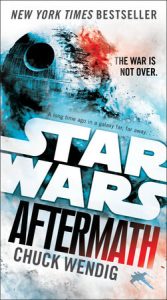

The second Death Star is destroyed. The Emperor and his powerful enforcer, Darth Vader, are rumoured to be dead. The Galactic Empire is in chaos….Optimism and fear reign side by side.

The second Death Star is destroyed. The Emperor and his powerful enforcer, Darth Vader, are rumoured to be dead. The Galactic Empire is in chaos….Optimism and fear reign side by side.