If you’re North American you likely know the story, or at least parts of it, even if you’re not a sports fan. Lou Gehrig was not, once upon a time, the name of a disease. He was the Iron Horse, one of the most lethal of the famed “Murderer’s Row” batting lineups of the New York Yankees of the 1920s and

‘30s. One day, an early part of the Gehrig story goes, the Yanks’ first baseman Wally Pipp needed a day off, and a young Gehrig filled in admirably. 2130 games (and 14 seasons) later, he asked to be taken out of the lineup in May of a strangely ineffective ’39 season, and within weeks had had confirmed a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), still known to many as “Lou Gehrig’s Disease”. On July 4, 1939, Yankees fans were given their chance to say farewell. By 1941 – on the same date that he replaced Pipp on his way to becoming baseball’s greatest-ever first baseman – he was dead, days before his 38th birthday.

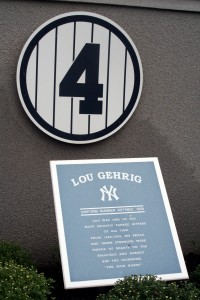

Gehrig was a two-time MVP, six times a World Series champion, a Triple Crown performer, and still holds a gaudy string of all-time batting records for a first baseman. His famed consecutive-games streak was, beyond improbably, finally broken only in 1995 by the great Orioles shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. in 1995. (He played shortstop, the most physically demanding position in the sport. Incredible.) Therefore, it is odd, but a necessarily startling reality check, that Gehrig is remembered best for what killed him, and for the manner of his exit from life and from the game he loved. Grace. Humility. Courage. Dignity. All were on display that Independence Day in New York, when he gave a speech that still rings nobly and true. It’s hard to imagine modern athletes summoning such plain-spoken eloquence.

Babe Ruth had already praised him. Yankees field manager Joe McCarthy

The Babe, already retired, embraces Gehrig. His number 6 would later join Gehrig’s 4 among the Yankee Stadium monuments.

loved him like a father, and turned in tears from his prepared thoughts to sob, “Lou, what else can I say except that it was a sad day in the life of everybody who knew you when you…told me you were quitting as a ballplayer because you felt yourself a hindrance to the team. My God, man, you were never that.”[When Gehrig’s turn came, he famously began this way:

“Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans.”

A bad break. Goodness. We know ALS as a death sentence, inevitable and torturous. Gehrig called himself a lucky man for what he had been given, and insisted later that he was not “depressed or pessimistic about my condition….I intend to hold on as long as possible and then if the inevitable comes, I will accept it philosophically and hope for the best. That’s all we can do.” He was archetypal: the athlete as wise and humble man, the Iron Horse as Stoic philosopher. His first statement begins and ends with the “fans” and their kind encouragement, and would we be likely to hear that from a player in this more cynical age?

“Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn’t consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I’m lucky. Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To have spent six years with that wonderful little fellow, Miller Huggins? Then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy? Sure, I’m lucky.”

The speech has rhythm. Look at that classic series of questions, in which he names the owner, the general manager, and then the two dugout generals of the Yankees squads he had played for. Look at his repetition of Sure, I’m lucky. I imagine him waving an outstretched left arm toward his teammates, acknowledging “these grand men”. Grand. What a shame we’ve lost that brief but evocative word from the language; it’s only used in irony now. I miss fellow, too, such a warm word, embracing the other as equal sharer and companion. (Hmm. Have American Presidents used “My fellow Americans” since the disgraceful days of Richard Nixon?)

“When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift — that’s something. When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies — that’s something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own daughter — that’s something. When you have a father and a mother who work all their lives so that you can have an education and build your body — it’s a blessing. When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed — that’s the finest I know.”

The speech rolls on like the sea here, with the tidal repetition of five whens, but look at the rhetorical skill he uses when he moves from the three “that’s something” statements – from a time when you’re really something! was high praise, indeed – to the “blessing” of his family and a wife who exemplified for him “the finest”. Something: the quaintness of the Giants being a New York team, or white-coated peanut-sellers, or a mother-in-law coming in for such singular praise. I love his “build your body” phrase, and how he put “education” right next to it. (He went to Columbia, after all, though he didn’t graduate.) Gehrig was immortalized for his courage, above all, and yet notice how he humbles himself before that shown by his bride. (She never re-married. She lived until the 1980s, and spent her time mainly in support of research into and families afflicted by the disease that claimed her husband. Her name was Eleanor.)

“So I close in saying that I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for. Thank you.”

That’s salt of the earth stuff, right there. I’ve never seen the iconic, no-doubt schmaltzy 1942 film The Pride of the Yankees with Gary Cooper as the Iron Horse. That’s okay with me, because from all I read – especially those gracious words that he spoke himself – who wouldn’t have been proud to be a fellow American, a fellow sportsman, a fellow human beingto such a grand man as Lou Gehrig, even without Hollywood? His pin-striped number 4 was the first athletic uniform to be retired. May his dignity never go entirely out of fashion.

Such a moving story. Thank you for sharing this with us. He provides an example we would all do well to emulate.