[3-minute read]

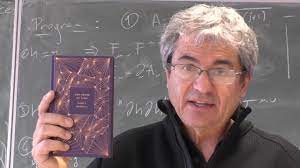

Rovelli is a physicist who inhabits a realm of thought I couldn’t find with any GPS. Grade 12 physics had already left me behind. But Rovelli is an intellectual star, with a degree of celebrity from a series of articles he’d written for an Italian newspaper; Seven Brief Lessons on Physics became a slow-moving international sensation. It has been on my vague gotta get around to that sometime list for about five years. I was surprised and impressed to find Rovelli’s Reality is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity among the books I picked up from the library for my enterprising life partner, who is even less science-literate than I am. (N.K. Jemisin’s fantasy novel The City We Became was a choice she struggled even more to explain; knowing a bit more about quantum physics suits her pragmatism better than fantastical battles between eccentric good and brooding, yucky evil, even though she loves New York City. Yup, I’m reading that one, too.)

I thought I’d try to be pragmatic. I would read the introduction to Reality is Not What It Seems during a half-hour walk to the library. That would do it: grasp the basic outlines of the physicist’s thinking, pop the thing in the Return slot, and bypass the thornier bits to come. Good plan! It didn’t work, because Rovelli writes with grace and conviction as he outlines the ancient roots of the bewildering investigations of modern physics. Reality is Not What It Seems, written before Seven Lessons, has been widely translated after the success of the Seven Brief Lessons that followed it. It is profoundly engaging. I was all the way in after reading this portion of “Walking Along the Shore”, Rovelli’s introduction to the Reality of quantum gravity. (Yes, I’m going to be reading about quantum gravity. I’m 70 pages in, have winged from Democritus to Newton and am now beginning the summary on our dear 20th-century friend Albert. My brain has not yet been broken.¹ It’s a wonderful read.)

In his introduction, Rovelli recalls Plato’s allegory of The Cave. Remember? One man escapes his chains, leaves the cave and encounters initially blinding new vistas, a sequence of approaches to “reality” he couldn’t have imagined from the cave’s shadowy depths. He “returns excitedly to his companions, to tell them what he has seen. They find it hard to believe.” Plato’s philosopher-king, the one who transcends the limited understandings of his benighted companions, is Rovelli’s image of the scientist:

“We are all in the depths of a cave, chained by our ignorance….If we try to see further, we are confused; we are unaccustomed. But we try. This is science. Scientific thinking explores and redraws the world, gradually offering us better and better images of it, teaching us to think in ever more effective ways. Science is a continual exploration of ways of thinking. Its strength is its visionary capacity to demolish preconceived ideas, to reveal new regions of reality, and to construct new and more effective images of the world. This adventure rests upon the entirety of past knowledge, but at its heart is change. The world is boundless and iridescent….We are immersed in its mystery and in its beauty, and over the horizon there is unexplored territory….[O]ur precariousness, suspended over the abyss of the immensity of what we don’t know, does not render life meaningless: it makes it interesting and precious.”

Carlo Rovelli, Reality is Not What It Seems, p. 8

To think in progressively more useful ways. To refine our perception of what truly is. To refuse to be bound by traditional constraints on understanding. I love this poetic description of science.

I infer from much of his commentary that Rovelli is firmly anti-religion in his views, seeing the impulse toward faith as necessarily a reinforcement of tradition, authoritarianism and reason-held-hostage. I do think he’s mistaken in this, falling into the same trap religionists have, all too often; dogmatism among scientists has a long rap sheet of its own, some of which Rovelli recounts. However, I am no less attracted by his excellent, accessible explanations. I am also confirmed in my own unsystematic, accidentalist approach to deciding what I’ll read next. Good to meet you, sir.

¹ I spoke too soon. My brain pan started to leak noticeably last night, around page 72, as Rovelli explained Einstein’s special relativity to me. I’m not giving up yet, but it appears that my ability to roughly grasp physics ended in 1904. (Einstein was twenty-five in 1905, when he submitted three journal articles “each…worthy of a Nobel Prize”, according to Rovelli.)