I quoted John Steinbeck recently (in “He Said/She Said”, below right) because I empathize with the fear and inadequacy he felt as a writer. It’s always good to know that heroes are what they are not because they have “no fear” – that great modern lie of the superhero movies and shoe-hawking T-shirts – but precisely because they do fear and it doesn’t stop them. His writerly doubts came as he was struggling with an experimental novel, the classic Of Mice and Men, and I read about them in its introduction. Then I dived, certainly not for the first or second time and (swear to God, hope not to die) likely not for the last, into Steinbeck’s timeless evocation of rural California, sometime early in the 20th century.

It was a time of migrant workers. Steinbeck had written of the Depression-desperate men flooding California in search of farm work, and of the battle between union organizers and landowners, in one of his first commercial successes, In Dubious Battle. It was a detached, bird’s-eye view of the struggle – “curiously bloodless”, as one commentator put it – in which leaders on both sides were shown to be self-interested and heedless of the suffering of the migrants. Of Mice and Men came out in 1937, and although it was concerned with the same economic and geographic landscape, its approach was completely different: localized, brief, and personal. Steinbeck, while writing it, was already engaged in active research – working on farms, interviewing labourers and owners and union activists – that would eventually lead to the monumental story of the migratory Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939.1 The books are not a true trilogy – there are no continuing characters – but they represent three views of the same history.

The title of the short middle novel – a novella, really, as it barely exceeds 100 pages – comes from the Robert Burns poem “To a Mouse”. Having disturbed the mouse’s den with his plough, the speaker muses that “the best-laid plans o’ mice an’ men” often go wrong, leaving nothing but “grief an’ pain”. I hope this is not a spoiler, but it may not surprise you that Of Mice and Men is not a joyful read, but my goodness, it is a justly famous and a moving one.

George Milton and Lennie Small, as the novel opens, are on foot, cursing a bus driver who has dropped them off miles from the farm where they have been hired to work. George does all the complaining, and as throughout the story, most of the talking for the pair, too. They travel together, offering their muscles to farming operations; Lennie, a huge but childish man, has most of the muscle. George decides they’ll camp out by a river that night, in a spot where countless men have stayed, a hobo “jungle” with drinkable water, shade, a horizontal tree branch to sit on and the remains of countless campfires. Just as their fellow ranch hands later do, we try to puzzle out the relationship between the two men. Lennie thinks and speaks like a child of five or six years, and apparently his fateful combination of low intelligence, childish fears and murderous strength has gotten the two in trouble before.

As an antidote to their scarce and sometimes scary life, George is again persuaded during that last peaceful night to tell Lennie’s favourite story. It clearly appeals to George, too, for different reasons. “Guys like us are the loneliest guys in the world”. “But not us!” Lennie typically interjects joyfully. Not them. George rhapsodizes about a life in which men look out for each other, reap the fruits of their own labour and “live off the fatta the lan’”, where there is home and choice and companionship that lasts longer than a few weeks of farm work or a few hours in a cat-house. When George tells it, Lennie is antsy about the existential details. As a five-year-old might be, he can’t wait for George to “tell about the rabbits”. Lennie loves to touch soft things, longs to care for rabbits, and doesn’t understand why small animals die or girls scream when he innocently strokes them with his enormous hands.

With visions of bunnies dancing in Lennie’s head, and dreams of dignity and ownership swelling in George’s, they sleep by the banks of the Salinas River. The next morning, they trudge the last few miles to the farm, where they are grilled by the crusty owner but ultimately accepted as workers; Lennie’s size and George’s testimonials to his strength get them work, even though most are suspicious of two men who travel together. (There is no hint of homophobia here, just the oddity of it. The boss suspects George of exploiting Lennie financially, and it is one measure of the excellence of the novel that we can’t completely dismiss this possibility.) “It’s like that, is it?” says the owner, eying the odd couple. “Yeah, it’s like that,” says George in the terse, indirect and often blasphemous speech of working men among men. Such dialogue is one of the chief attractions in Of Mice and Men, and a reward for re-reading. Steinbeck’s journals show that he was experimenting with a way to make a novel read like a play – a limited number of scenes and characters, but with fiction’s greater ability to background personality and situations – and a Broadway version won awards within a year of the book’s publication.

On the farm, they soon meet Curley, the boss’s son, a “handsy” little man with some boxing success in his back pocket, and an insecurity that leads him to bullying cruelty. Like everyone but George and Lennie, Curley is given no surname. His pretty young bride, for whom he is always looking and forever jealous on a ranch full of men, is never called anything but “Curley’s wife”, unless it’s “jailbait” or “tart”. (I’d forgotten this, but Of Mice and Men remains one of the most banned books in American history; its blunt male language and frank references to prostitution, for example, were shocking for decades after publication and were toned down for stage and screen.) Carlson is

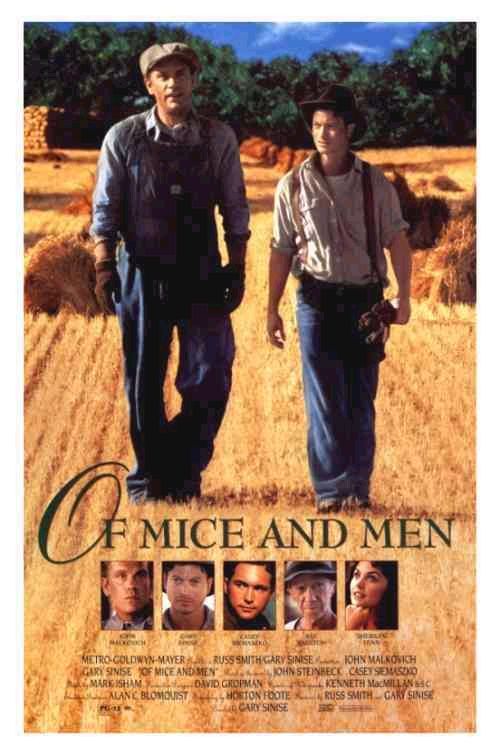

Malkovich as Lennie, Sinise as George, and “My Favorite Martian”‘s Ray Walston showing that silly TV popularity is not the end of an actor’s career, here playing Candy.

another farmhand, a minor character most notable for owning a gun. As Chekhov famously said of theatrical necessity, “One must not put a loaded rifle on the stage if no one is thinking of firing it,” and the novel’s play-like quality shows here in a disturbing bit of foreshadowing that is Carlson’s main contribution to the plot. Candy is a crippled old man, injured in a farm accident and kept around to sweep the bunkhouses. His only real company is a blind old sheepdog, since he doesn’t really fit with the younger men on the ranch. At first, he’s such a marginal figure that he manages to overhear one of George’s retellings of the “guys like us” reverie, and desperately longs to share the homestead dream. The only lonelier character than him — unless it’s Curley’s wife — is Crooks, the black (and also crippled) stable hand, whose skill in pitching horseshoes gets him some brief and bounded acceptance, but who lives in a tiny nook in the stable, next to the manure pile. There isn’t even bunkhouse camaraderie for the “nigger”.

Crooks, understandably, is a bit cynical about dreams and resentful of anyone with even the prospect of real companionship. So is Curley’s wife. She brags of how she “coulda bin in pitchers”, mainly in a desperate bid to be noticed and appreciated more than she is by her similarly self-absorbed and cocky brute of a husband. Steinbeck contrasts their cynicism with the hopes of Lennie, George and then Candy.

In the midst is the only character I don’t entirely buy, the only one besides George and Lennie to have a name that doesn’t start with ‘C’. Slim is a “skinner”, the guy who leads the mule teams during harvest and planting. He is quiet, handsome, perceptive and universally respected. For me, Steinbeck goes a bit far, telling rather than showing, with Slim’s “god-like” pronouncements being the final word among the men. He is an appealing and necessary character, occasional too-obvious adjectives aside, and it is through his eyes that we get confirmation or dismissal of our own assessments of characters and situations on the ranch. More importantly, it is Slim’s subdued but sought-after viewpoint that authorizes two linked, bitter and inevitable sacrifices that key characters eventually make.

All that we meet, except maybe Slim, are lonely and insecure. Some are thinking of better, and some are sure that better doesn’t exist. Together, especially with Lennie’s innocence and size acting like a red flag to Curley’s surly little bull, they make for a toxic character stew. Lennie begs, “George, le’s get outta here. It’s mean here.” They eventually do, but not before the ranch is visited by violence and death, and not before George and Lennie’s history returns to haunt them. “I done a bad thing,” Lennie moans to himself. “I done another bad thing.” And not long before their doomed escape from the ranch, George bleakly surveys the shambles of their homesteaders’ dream, lying in a quiet corner of the stable, and mutters to nobody in particular, “I think I knowed we’d never do her.” This is not a dream deferred, but pathetically gutted and disbelieved in hindsight. It’s one of the most heartbreaking lines in the novel.

Of Mice and Men is a brief but intense read, and one of the easiest instances in which “reading the book before I see the movie” can be done with little fuss, especially for those reluctant to take on a fat piece of fiction.2 This one is lean, condensed and easily digested, though it will nourish your thinking for days. I found it especially vivid this time, living as I do in a country where migrant labour is such a potent and ubiquitous fact of life, and at a time when the American southwest is again struggling with the problem of economic disparity: the U.S.A.’s material “promised land”, as it long has, attracts the desperate attention of those from less fortunate terrain, looking for an honest break. Steinbeck compels us to care for George and Lennie, for Candy and Crooks and even for Curley’s radioactive wife, and perhaps by extension we find sympathy for the dispossessed and those who can’t find home, especially when financial uncertainty and migrant labour are so much on our minds.

1 The Grapes of Wrath still sells steadily. What a cultural impact it has had in the United States! John Ford won the Best Director Oscar for the 1940 film, which helped make a major star of Henry Fonda, who played Tom Joad, the lead character. Woody Guthrie’s first well-known album in 1940 featured “The Ballad of Tom Joad”, and Bruce Springsteen won a 1995 Grammy (Best Folk Album) for The Ghost of Tom Joad. Rage Against the Machine made the same song the title piece of a later album. The Steinbeck novel, when the 70th anniversary of its publication arrived in 2009, seemed as powerful as ever in the wake of the financial crisis, and even inspired a series in the U.K.’s Guardian newspaper that travels along the famous Route 66 taken by the Joads. Steven Spielberg is reportedly planning a film remake of the story, likely timed for the 75th anniversary of the book’s publication.

2 There have been three films, the first coming out in 1939. Burgess Meredith, decades before his campy TV ‘Penguin’ or his Oscar-nominated role as the fight trainer in Rocky, was George Milton to Lon Chaney Jr.’s Lennie Small. In 1981, Robert “Baretta” Blake teamed with Randy Quaid in a made-for-TV flick. I haven’t seen either of them, but I can only hardly imagine anybody else in the roles because the 1992 feature film was superb, with Gary Sinise directing and playing George and the eccentric acting treasure John Malkovich being Lennie Small.