Reviewed, in the usual not-even-trying-to-be-timely way:

Tuesdays With Morrie: An Old Man, A Young Man, and Life’s Greatest Lesson by Mitch Albom

Morrie Schwartz was good medicine, and he still is.

I was late hearing the news about the killing spree at the University of California at Santa Barbara, blessed in part by our cultural distance in China, to some degree by immersion in another project, and otherwise by finishing my re-read, on a recent Tuesday, of Mitch Albom’s 1997 publishing phenomenon. There aren’t many better prophylactics against the infections of toxic dismay, rampant disillusion and untargeted anger than this slender, absorbing memoir.

I’d been pretty quick, for a chronically tardy retro-reader, in getting to Tuesdays With Morrie the first time around. I was a high school teacher and basketball coach back then, and even best-sellerdom couldn’t discourage me from picking up a book with a subtitle like that. Besides, Albom was the young lion of American sportswriting, and I’d read of few of his columns that had been re-printed in Canadian papers. (This was in the late ‘90s, when the ‘Net was no biggie. I was starting to reluctantly concede that “electronic mail” was pretty useful. I still liked licking stamps and envelopes.) I knew he was good, and I wanted to get to know who this Morrie Schwartz was. I’m sure I gasped and sniffled more than a few times back then, but I have the feeling that Morrie “got to me” even more this recent second time around.

It’s a simple story, really. A tightly wound young man at Brandeis University shuffles into a sociology class taught by Professor Schwartz. It’s an unusual course, asking students to learn the theories of how societies function, yes, but also to become part of a small experiment in thoughtful discourse, team building, and living a socially enlightened life. Student gets hooked. Student finds father figure. Professor sees reminders of a younger self. Graduation is an emotional parting on both sides. Promises are made.

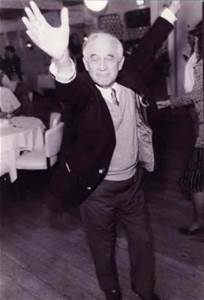

Even after “Tuesdays”, “Five People” and such, he’s still a jock star on ESPN’s The Sports Reporters.

Sixteen years later, Mitch Albom was as close to a rock star as a sports grunt gets. He’d written a half-dozen books, won shelves full of national awards for jock journalism, and TV and radio loved him. (He’s been named the top sportwriter in America 13 times.) He was winning the rat race, from his Detroit Free Press office and in the material trappings of a comfortable house, with all the trimmings. By a fluke, one restless evening by the TV, he channel-surfed onto a story wave that was about to become an unusually quiet and dignified American sensation: a retired professor, dying inexorably of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis – ALS, “Lou Gehrig’s disease” – was using his own life’s end as a research project. He had decided that he “would walk that final bridge between life and death, and narrate the trip”. It was Morrie Schwartz, of course, on Albom’s television, and a 30-something Mitch remembered his promise to stay close with the best teacher he’d ever had. He hadn’t. He suddenly felt not like a winner in the social race, but just a rat.

He felt ashamed, chagrined — what happened to me? — but he got on a plane. It wasn’t a Tuesday, and he didn’t feel remotely ready when he arrived at Morrie’s home outside of Boston. Professor Schwartz, though, seemed to remember more about one of his thousands of students than Albom did himself: how a young Mitch had called him “Coach”, that both of them had younger brothers, how they “were Tuesday people” who’d spent most of their class and consultation time together on that day. A lengthy labour strike at Albom’s paper, serendipitously, unchained him from his desk, his phone and his feverish, keep-the-devil-at-bay approach to his work. Albom asked to come back and visit a second time, Coach suggested the following Tuesday, and so began one of many tutorials Schwartz was conducting with colleagues, former students, and several times with a large national TV audience.

Tuesdays With Morrie is framed as the dying teacher’s last course. The brief introductory chapters – “The Curriculum”, “The Syllabus”, “The Student”, “The Classroom” – give us our orientation to the two men involved, their relationship, their wives, their similarities, and the differences that Albom is at pains to point out. He pairs Schwartz’s belief in him (“you’re a good soul”) to his restless self-doubt, Morrie’s concern for others with his own self-involvement, and the professor’s open-hearted generosity of spirit to the driven young professional’s under-nourished and tensely guarded heart. By the time, though, that Albom makes his third visit, he is, besides feasting at his beloved mentor’s banquet of wisdom and warmth, also convinced that “I had to do something”. The book – which the young “player” was able, with difficulty, to sell to a publisher before his Coach died, ensuring payment of his medical bills – was the result. “Shall I tell you what it’s like?” Schwartz asked on the first visit. He meant dying, of course, and everything that goes into it – which, to him, was all of life.

What follows is Mitch Albom’s carefully recorded, lovingly distilled results of fourteen Tuesday encounters with a steadily declining, relentlessly generous teacher.

- We Talk About the World. “Ah, Mitch, I’m gonna loosen you up. One day I’m gonna show you it’s okay to cry.”

- We Talk About Feeling Sorry for Yourself. “I don’t allow myself any more self-pity than…a little each morning, a few tears, and that’s all.”

- We Talk About Regrets. “The culture doesn’t encourage us to think about [important] things…so we don’t get into the habit of standing back and looking at our lives…”

- We Talk About Death. “The truth is, Mitch, once you learn how to die, you learn how to live.”

- We Talk About Family. “As our great poet Auden said, ‘Love each other or perish’.”

- We Talk About Emotions. “If you hold back on the emotions…you can never get to being detached, you’re too busy being afraid…”

- We Talk About the Fear of Aging. “I embrace aging….Aging is not just decay….It’s growth.”

- We Talk About Money. “We put our values in the wrong things. And it leads to very disillusioned lives.”

- We Talk About How Love Goes On. “I was thinking of this [for my tombstone]: A Teacher to the Last.”

- We Talk About Marriage. “You get tested. You find out who you are…”

- We Talk About Our Culture. “People are only mean when they’re threatened, and that’s what our culture does. That’s what our economy does.”

- We Talk About Forgiveness. “Don’t wait, Mitch. Not everyone gets the time I’m getting. Not everyone is as lucky.”

- We Talk About the Perfect Day. “How could he find perfection in such an average day?”

- We Say Good-bye. “Okay, then.”

Throughout the book, it is this compassionate, constantly curious and ever-gentle teaching voice that we hear. Albom takes us on short, illuminating field trips as well: his estrangement from his brother, tales of Morrie’s difficult youth and colourful career, and the TV interviews with the famed Nightline journalist Ted Koppel (“The Audiovisual”, parts one to three).

But it is always Morrie’s words that we come back to. The genius of the book is its simplicity, in the compelling but unobtrusive way that Mitch Albom sketches for us the life and the courage of his teacher, “the father everyone wishes he’d had”, as well as the effect he was having on his former student, on all the people who were in contact with him.

Morrie Schwartz was A Teacher to the Last, and well beyond – and not only because of the eventual world-wide success of Mitch Albom’s book, and the subsequent film and various theatrical productions. In a tenth-anniversary afterword he wrote in 2007, Albom jokes that the constant reminders of what Morrie has meant to millions of people are now his penance for having not seen his Coach for 16 years. He speaks and hears of him constantly. He misses many things, and perhaps most — something this review also misses — the humour, Morrie’s love of laughter, how much of even their last few sessions together were spent giggling over the lamest jokes.

This was one of my favourite bits of Schwartzian humour and pathos. He asked Albom to still visit him once he’d died. On Tuesdays, of course. “Tell you what,” he told his special student. “After I’m dead, you talk. And I’ll listen.” I don’t doubt that his young Player still takes him up on that offer, but thanks to Albom, we still get to listen to the Coach, too. And (spoiler alert!), Morrie Schwartz did get to Mitch Albom, just like he got to Ted Koppel, and just as I’m taken sniffling hostage by this fatherly voice just about every time I open the book.

My GOODNESS, we need our teachers. Our fathers. A Coach. If you’re short in any of these areas – and even if you’re not – Tuesdays With Morrie still makes for surprisingly upbeat, enjoyable and enlightening reading. It can be taken in small doses, or in one steady intravenous drip. It only takes a few hours. You’ll feel good. You’ll cry a little. You’ll feel better. You’ll have Morrie in your ear, and maybe a tear in your eye.