**(Lest We Forget)**

The campaign is over now.

There have been several concerted efforts to raise global awareness. One proclaimed the passing of 10,000 hours of unjust, of ridiculously tragic imprisonment of seven Baha’i leaders in Iran. Many fine words were said in numerous dignified contexts, but the “Yaran” – it means “friends” in Farsi – remained in jail. The five-year mark of their astounding 20-year sentences brought another crescendo of polite indignation, but these five years of loss, not only to the persecuted Baha’i minority but to all of Iranian society, moved the Teheran government not a bit.

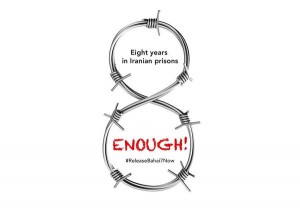

In May of 2015, the hashtag #SevenBahaisSevenYears achieved not quite the currency of, say, #BlackLivesMatter (to say nothing of tags for TV shows or celebrity break-ups), but it circled the globe with awareness and a renewed call for justice. Earlier this month, #EnoughIsEnough and #ReleaseBahai7Now had their moments of trendiness as the Yaran’s captivity reached its eight anniversary.

The campaign did its best. More people than before are aware of the human rights situation in Iran, one that puts the Baha’is at the centre of the issue – not that they are the only, or even the largest, group that is oppressed and unjustly incarcerated. In fact, the Baha’i community wishes only to serve the broader population, and is dogged, even when its brightest young people are excluded from university admission, in its pursuit of education for all. Their “crime” is one, plainly and simply, of belief in the teachings of the 19th-century Persian nobleman known as Baha’u’llah, considered a heretic by Shiah Islamic clerics. All the noise about “sedition” and “immorality” and “spying” is nothing but bigoted, ignorant and baseless slander; religious intolerance is the reality.

So here I am. I tweeted and liked. Did my bit, I guess. Maybe so.There’s basketball practice tonight, and I really ought to get the lawn cut. Lord knows we all have things to do, but I’m saying it again: there are seven men and women who’ve entered their ninth years in prison, people I never expect to meet but who have become my own personal Quietly Magnificent Seven, heroes of justice and peace and doggedly loving resistance to giving in to hate, succumbing to fear or despair. I’ve written about each one, in tribute but also for the training and elevation of my own character. (So much work to be done.) Here’s what I remember most. I wrote about each at the 7-year mark of their absence from Iranian society. I’d love for you to read about them again:

Afif Naeimi is like me: he didn’t get into medical school, but not because he stunk up his chem and bio labs. He’s in his mid-50s. He’s a good friend of Frank, a guy I used to work with some. One degree of separation, or less.

Behrouz Tavakkoli got fired from his government position on a DSWWB conviction (doing social work while Baha’i). He’s 65, but there’ll be no pension. He’d likely be called “Bruce” if he was in Canada, and that got me meditating on Cockburn. And then on Mark Knopfler, and how Mr. Tavakkoli feels to me like a “brother in arms”, but it’s not all about Actually Great Songs from the 1980s. It’s also about a great man who worked as a carpenter.

Saeid Rezaie has two daughters who’ve been arrested for running literacy programs for poor kids, and a son whose had no father during his adolescence. He’s my age, and his thwarted work in agriculture reminded me of my hometown. Another Brother.

Fariba Kamalabadi’s story made me particularly sour about her alleged criminality. (Warning: sarcasm.) Her “confession” is stunning, noble and fearless. She missed her daughter’s wedding, but that’s years ago now.

Jamaloddin Khanjani is into his 80s, and all he’s missed is the funeral of the woman he was married to for over 50 years. (That’s not all he’s missed, or that his country has.) His stubborn life of service is central to the greatest under-told story of grassroots and divine democracy imaginable: that of the elected Baha’i assemblies in the early years of the so-called Islamic Revolution in Iran.

Mahvash Sabet was a Psych major and a teacher; I feel close to her as a result, but am far from her level of service. Prison turned her into a poet, but her life before and in prison has been about education; she led the underground Baha’i university for those not allowed higher education by their country. In her 60s, her face is lovelier than ever.

Vahid Tizfahm is the youngest of the seven, and has a son in high school, about the age of my youngest. His letters – to the son that misses him, and to the country he still loves, despite all it has done to him, his family and his community – are magnificent. The Quietly Magnificent Seventh.

How long, Iran? How long, O Justice?