This is part two of “Crossing the Street in China”. The less-violently-so-but-still emotional part one, on going out of the Way by bringing “poker” into a Chinese college classroom, was here.

In one week, we fly from Dalian to Beijing to Toronto to Ottawa. We’ll be “home”. Our China sojourn, five years young, ends in seven days. I’ll be posting about that, too. I hate goodbyes, and we’ve already had dozens of ’em, but I won’t miss the kind of experience I recount below.

* AltTitle: Fear and Loathing on Huangpu Lu

It’s another T.I.C. story. My wife and I mutter TIC (“this is China”) with resignation, a shrug, usually with grace and occasionally with genuine wonder. (It’s an amazing place. So much to see and learn. But.) Perhaps my most emotionally rich TIC moment happened last week, too, if by “emotion” you mean volcanic but helpless rage.

A Good Guy, defined: someone who goes out of his way for someone else. My son regularly goes out of his way, though not for the sake of being a gentleman, to avoid crossing the main street near our home. Huangpu Lu is six lanes wide, with a bus stop on either side, and the car-heavy side street that comes from our large apartment complex enters it on an oblique angle. There is no stoplight. There is a painted zebra-stripe crossing, which means nothing in China. (Not quite true. It means that drivers speed up as they approach it so pedestrians won’t try anything stupid, like trying to cross ahead of their Audis.) My son doesn’t need to cross there as a rule, and refuses to. Last year, he saw what he’s convinced were three dead bodies at that crossing, one a mown-down pedestrian, two in a car wreck with blood staining the road for several metres.

I cross Huangpu Lu at this spot every day that I go to school. I could cross later, but the near side of the street is always more crowded, plus there’s a 200-metre stretch with no sidewalk, where pedestrians have to walk a 2-metre gap between traffic and the natural stone wall cut out of a hill. It’s not so bad in one direction; I can see the traffic coming, and imagine heroically nimble dives into the ditch. (Yup, too many bad movies. Too much sandlot and high school football.) I try never to walk it on the way back. I want to see that truck with my destiny written on its bumper. So, I nearly always cross to the other sidewalk.

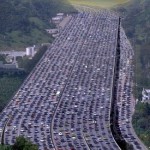

An epic Chinese highway jam. My street’s not this wide, though this would’ve been easier to cross. So slow.

My wife and I crossed that day. Traffic wasn’t too bad, and that’s dangerous. (Did I mention that the street is a downhill slope?) A bus pulled into the stopping lane for boarding. We walked in front of it to the edge of lane one. No cars were trying to veer around the bus to turn right onto our street. So far, so good. We walked, along with one other person (in China, pedestrians gather for strength in numbers, a little flotilla of rowboats crossing a supertanker shipping route), across lane one the first chance we got. We probably could have taken the second as well, but a car was coming fast from our left and there was a larger gap behind it. It passed, and we trotted across the second lane; I could see that the next guy in lane 2 was barrelling along even faster, so we hustled. Besides, the third lane was clear, so I wanted to get across that one at the same go. I glanced to the right, checking for left-turning cars coming out from our street behind us, as well as sussing out the flow coming from the other direction, the next three lanes we had to cross.

My wife screamed from my right, and just behind me. I jerked my head back to the left, and suddenly saw that Mr. Leadfoot was not only accelerating, but he’d swung into lane three! He was anticipating his next pass, and somehow managed to miss that my wife and I had already crossed the lane he’d been in. I was caught halfway across the third lane. I hit my brakes, and I did something I never do. Aging athlete losing a step to Father Time? Dalian dust combined with oil spewn by badly maintained buses? Too much in my backpack? Sheer terror? I don’t know, but I slipped and fell down, right in front of that careening black car, hung out to dry, flat on my ass. No nimble dodges available, no action-hero tricks. (And that thing about your life passing before your eyes? Nosirree, though for my bride, the whole thing seemed to take minutes and I fell in super-slow motion. To me, it was a momentary blur. A second or two. Max.)

No brakes squealed. I suppose he braked to some degree, but in typical Chinese fashion the bastard swerved back into lane two, still at speed, and went right behind my bride. I lost my nut completely. Call it the fight or flight or turn the air blue response. The guy slowed down a little for a look in his rearview mirror. I should have gotten his plate number, but instead I roared imprecations I didn’t even know I remembered. I wanted to chase him down the street. I wanted to haul him out of his car. (Yes, it was black, the preferred colour for showing Party affiliation or other forms of conspicuous power. Yes, it was trophy-expensive.) I wanted to backhand him hard, shove his face down below his steering wheel and introduce him to his f–ing brake pedal. It was everything I could do not to chase after him, which would have been a pretty sight, pursuing a car down a Dalian street, swinging my backpack in one hand and a fist in the other.

I’m sure I was pretty enough, post-thrusting fingers and raging invective, as I stormed my way across the busier three lanes of traffic coming from the other direction. I didn’t kick or Thor-hammer any cars on the way, though I wanted to. I shouted at taxis – they’re the most dangerous of drivers, slaloming their way from lane to lane (or even sometimes sidewalks), always preferring horn and wheel to braking; the saving grace is that cabs are small, and have economical, gutless engines. I glared and snarled at startled, spoiled housewives. I gained the sidewalk. I desperately needed to throw something, such is my jock background and the neurochemical storm in my brain, but I managed to remember that my laptop was in my knapsack. I punted a municipal garbage/”recycling” bin with heroic force. It didn’t move far. It was five minutes before I was again incapable of assault and battery. Adrenaline is a strong sauce.

I’ve often laughed at the things my over-protected, only-child Chinese students think are so dangerous. (The sun. Standing on a table in class. Basketball.) “Come on, guys!” I grin. “The most dangerous thing in China is crossing the street! Shoot, or being in a car with no seatbelt – that’s how thousands of people die every year. Or, like, breathing.” I try to make a joke of it. That was a little harder to do, for the next few days.

And, as promised in part one, a joke.

Q: Why did the Chinese chicken cross the road?

A: Because bungee-jumping gets boring after a while.

Ha.