Tracy McGrady has announced his retirement, and it’s a black-armband day

Despite years of mediocrity, it was still a story. He was exciting, and such a perfect foil for “what if”s and “if only”s.

for Chinese basketball fans. (Some NBA snobs would say it’s his second retirement, the first being when he came over to Qingdao to play for the Double Star Eagles in the short Chinese Basketball Association season. I would not say that, as I need all the Chinese friends I have.) I’m certain that tears were shed in more than one Middle-Kingdom man-cave, though T-Mac also had a surprisingly big fan-club of starry-eyed young women, too. For a North American, the scenes of his arrival in and departure from Chinese airports were astonishing to watch, even in small doses. “TracyMania”, it was.

While he doesn’t inspire that sort of devotion in America, and certainly not among most Canadian ball-watchers, there’s no time to wait. Like greedy relatives who want to know the contents of the will before the deceased is even cold, writers and fans in the West vault instantly past any of the routine thoughts we have when someone we care about retires. So, what are you looking forward to? Does it feel good to be done? (When it comes to thirty-something men who have been incredibly well-paid for playing games, this would seem like a silly question, though I’m not sure it is, always.) And maybe we’d be bold enough to ask, Are you well set-up financially? How will you fill your days? What gives you a sense of purpose now? None o’ that, in the case of athletes we allegedly love. We are patently uninterested in any of those things. We don’t care a lick about what life for the famous dude will be like. The writers and fanboys go straight at the only question, it seems, that matters to us: is T-Mac a Hall of Famer?

America’s Greatest Fanboy – and one of its brightest and most interesting – is Bill Simmons, and he was in Full T-Mac Mode on Grantland recently. I was a little surprised at his resounding YES! to the HoF question. Honestly, my instant reaction to the will he or won’t he was a derisive snort (“are you serious?”), but reading Simmons made me realize that his selfish (and wrong-headed, he admits in hindsight) departure from the Raptors in 2000 had soured me on the young star more than I’d realized. (I was also, during the height of his career, paying much less attention to the NBA than I had in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, or for that matter during my last four years in China. In between, I was coaching the game so intensely that I rarely watched the NBA, and it was often such a knuckle-headed, individualistic era that I discouraged my players from watching it. “Who’s your favourite team?” they’d ask. “YOU guys!” I’d say.)

Simmons has not only a strong stats-based case for McGrady’s greatness, but an aesthetic one as well. He loved the grace, the unselfishness, and the ability to do a little of everything that T-Mac brought to the hardwood. (Plus, he could fly.) Simmons placed him just a notch below LeBron in this last do-it-all category of hierarchical appreciation. McGrady, even during his sometimes-passive last season in Qingdao, still moved beautifully, and like LeBron has my lasting respect for how well he saw the floor and how willingly and artfully he’d set up his teammates.

Numerically, Simmons offers some compelling and surprisingly favourable comparisons between the well-travelled T-Mac and the well-nigh-immortal Kobe Bryant – and not just during McGrady’s famously productive regular seasons, but also in the playoffs. Of course, he has been mocked for his career-long inability to get one of his teams past the opening round of the post-season. (In the CBA, the Qingdao Eagles didn’t even come close to qualifying during his one disappointing season.) After he signed with the San Antonio Spurs, he became a minor side-show of attention, especially on Chinese telecasts of Spurs games: Mai Di was mentioned with ridiculous frequency, given his infrequent and completely inconsequential chances to play. Smart-alecks dusted off the old “human victory cigar” gag, as he made his somewhat-sheepish entries into blowout wins. There was lots of self-righteous Internet tittering about his end-of-career “success” in advancing ultimately to game 7 of the Finals, which of course had nothing to do with him. It was about how good this Spurs team was. That sarcastic logic, such as it was, however, was not applied in reverse in examining why his previous teams — seven, if you count the CBA — weren’t playoff powers.

And here’s where that fundamental error comes in, especially in North America, where team sports reign but our approach to them becomes ever more individualistic. Rings. Good Lord, I’m getting tired of hearing about championship rings as the inevitable validation – or snobbish dismissal – of a man’s life in professional sport. Rings. So Derek Fisher, therefore, was better than John Stockton? (“Yeah! What did heever win?”) So Charles Barkley was nothing compared to, say, John Salley, winner of four rings on three different teams — with marginal playing time. Or “Big Shot Rob” Horry, with so many rings, and ballsy contributions as a role player on so many powerhouse teams. (Three different ones, for whom he had great moments, no question, but the guy still averaged 8 points per game in the playoffs, and never more than 13 ppg.) And I fell right into it. I mentally shared in the lazy “he’s not a winner” rhetoric, at least partly because he had bolted from a talented young Raptors

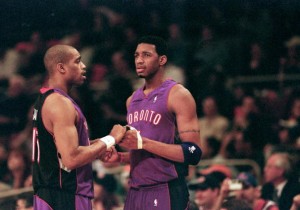

Vince and Tracy in purple. Mmm. So young, so athletic, so doomed by selfishness. Tracy flees to Orlando months after this 2000 playoff loss.

team, with some veteran character, at his first opportunity. He didn’t want to play in the shadow of “Air Canada”, his cousin Vince Carter, but man, if those two had found a way to play together… (Even lukewarm fans have long memories.)

Tracy McGrady, admittedly through his own fault at times but also via some spectacularly bad luck, played on some poor and mediocre teams. Even the Rockets, featuring Yao Ming (whom Simmons calls “the most overrated good player ever”), had a deeply flawed roster and Yao’s injury woes were growing. In the Grantland piece, Simmons exhaustively details the remarkably thin supporting casts that T-Mac had to work with. Blame marketing. Blame Michael, blame Kobe, blame Shaq, and now blame LeBron: too many NBA-watchers forget the basic calculus that it’s a team game. And McGrady, while he was winning those scoring titles, was still passing the ball wonderfully well, though he had to jack a lot of shots for those teams to be successful. And when playoffs came, he still had incredible numbers during his prime years, but he couldn’t do enough to drag his teammates to victory. Well, until his teammates were Tony Parker and Tim Duncan, but by then he was just along for the ride.

You might think the man was cursed: when he went to Qingdao to collect a few million, the mighty Eagles had just dismantled a decent team from the previous season, casting away most of their best Chinese players for reasons inscrutable to me. (Maybe it was simple: to pay McGrady.) The losing went on and on, until the CBA season was over and the Spurs gave him a gorgeous view of what a winning group looks like. (And curse strange caroms and Ray Allen’s game 6 miracle: the Spurs should have won!)

The more I learn of McGrady, the better I like him. I wrote about him here and here last season, using my perch in Dalian to observe his CBA tenure. (I also later compared his humbling return from China with the rise of a talented young Chinese player in America here — and no, not Jeremy Lin. He is American.) There is still adulation to be had and shoes to sell in China, where he can get paid more than an NBA club would offer. Apparently that door is still open, and maybe it’s a chance to keep playing a game he loves without having to find the flat tummy he used to have. Unlike most retiring pros, Tracy McGrady can continue to bank on his accomplishments and his fame. With chroniclers like Bill Simmons at his back, too, he will likely be remembered as one of the greatest players of his generation, ring-counters and disgruntled Canadians and potential-worshipping perfectionist coaches be damned.