[5-minute read]

#ObamasFavoriteWriter is the most reductive, semi-dismissive and ‘Net-friendly way to capsulize her, so I won’t. (Um…)

Let’s start this way: Before 2016, I had never heard of Marilynne Robinson, or at least her name never stuck to my brain casing. Now, I have read all four of her novels, listened to a lecture and two interviews, and read and re-read her Paris Review discussion and one book of essays while ploughing through a second, which was my main accomplishment yesterday and the day before. I think about her work, and about her – where does such a person come from? – constantly. I find myself pestering everybody I like whom I consider might be even a remote candidate to read her. She’s a glorious read.

It started with Phyllis¹. She is a retired university prof who decided, as one of her several voluntary teach-ins, to start a book-club looking at great modern fiction with spiritual themes and underpinnings — as if such literature could actually be found in what often seems to be a doubtful, jaggedly ironic and chronically disillusioned age. Surprise! It can be! Phyllis knew where to look. And so, I got to be the token male among a dozen-and-a-half thoughtful, quietly eager book-types. We read Louise Erdrich and Bahiyyih Nakhjavani and the conversations were fun and light-shedding.

¹ Nobody names a daughter Phyllis anymore, yet once upon an old time it was a beautiful name suggestive of green leaves and ancient Greek loyalty and goddess-love. Not bad, Phyll!

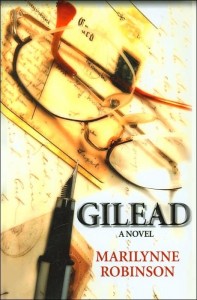

But mostly, we careened off on a helpless Marilynne Robinson jag. We couldn’t stop. We didn’t include her 1980 first novel, Housekeeping, which brought her critical praise and a “writers’ writer” designation and a faculty position at the University of Iowa. (I went back and read that one on my own, after I’d finished her Iowa-based sort of a trilogy but not really.) Our little group pulled its chairs up in a circle and started talking about Robinson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Gilead, which had stunned me and shaken the ground of American fiction at its 2004 publication – not that I noticed! (I show up late to some of the very best parties.)

Gilead came nearly a quarter-century after Housekeeping. I remember Frank McCourt’s reaction to questions about how late in his life his “overnight success” had come. (His 1996 memoir, Angela’s Ashes, was an international publishing sensation; he was well into his 60s when it came out.) “I was TEACHING,” he wrote, “that’s why it took so long!”² Robinson might give the same explanation, as she is a long-time faculty member of the legendary Iowa writers workshop. However, she has said in interviews that, not wanting to contribute shallow or derivative novels to the stream of American literature, she wanted to read. And think, as well as teach. And well she did, and does. She is a profound scholar: history, literature, religion, philosophy. Gilead, far from being a work that she laboured over for the intervening decades, came to her quite quickly in the voice of John Ames, a rural Iowa pastor.

² Ever grateful, I am, for McCourt’s lesser-known third book Teacher Man, an in-depth account of his locally legendary career as a high school English teacher in New York City. My review of Teacher Man has a special place, one of the few JHdotCOM pieces to run elsewhere before it ran here, and as a free-lance piece for which I Actually Got Paid.

The NY Times review is worth a read, if you’re hungry.

As I read Gilead, I kept asking myself, How is Robinson doing this? How can a novel about a Christian minister in a nowhere town even get published, let alone be this gripping and so smartly written? Simply put, it is a literary miracle, and our little group couldn’t stop, since neither could Ms. Robinson. She wrote Gilead – it is a tiny actual town in Iowa – as the letter that the aging Pastor Ames writes to his young son, the product of a strange, late and utterly unexpected marriage to a much younger woman. Ames wants to explain himself before he dies, so that the boy will, when he comes of age, know something of his departed father. As a novelistic result, so do we, as well as making other compelling acquaintances of the imaginary kind: Ames’s young wife Lila, his lifelong friend and intellectual sparring partner Robert Boughton, and Boughton’s troubled and troublesome son Jack. Robinson couldn’t get enough of these characters either, to our good luck and delight.

Within a few years, Robinson had returned to the same setting with another astonishing novel, Home. Some of the same ground is walked upon, but from a very different perspective. In Home (2008), Ames’s namesake, John Ames “Jack” Boughton, son of another local Gilead clergyman, has come back to town under unclear circumstances. Jack is the great mystery of Gilead, and of Gilead, and while he is central to Home, and while we discover much more about him than we’d been able to see in the earlier novel, he remains enigmatic. It is his younger sister Glory Boughton, also returned to the family home to care for her failing father, whose mind we have most access to in the third-person narrative. An amazing amount of the book is composed of conversations between the two siblings, who uneasily come to terms with their shared and private histories – amazing, primarily, because the novel doesn’t drag as a result. I would have wanted to go back Home again — and I will re-read it — except that Robinson still wasn’t finished, so neither were Phyllis’s Angels. (And me.)

Lila followed in 2014. This one is told from inside the remarkable mind of John Ames’s young wife, and the first-person narrative begins with some of the most instantly right there opening pages I’ve ever read. I didn’t know what was going on, but it was vivid, dangerous and weirdly believable. Lila’s narrative voice couldn’t be much more distinguished and separate from that of Ames, with the result that although we know where Lila is going to end up, it remains incredible and fascinating and dramatic that she does. Another miracle. I consumed this third book in the Gilead not-really-a-trilogy in a rush. (Can we call it a trilogy when it actually tells the same mega-story three times over?) The only reason that my reading group didn’t rush headlong into the fourth book of the series is that, well, there isn’t one. (Yet.) Ms. Robinson has given the most arid and subtle of hints – or maybe I’m just hoping too hard, and think that she has – that she is not yet done with Gilead, or especially with the ever-compelling Jack.

And shoot, for me, that was just the fictional start. The Paris Review is justly famous for its deep and erudite interviews with authors, under its “Art of Fiction” rubric. Number 198 is with Marilynne Robinson, and I was unsurprised but nonetheless stirred to find her insights deep, her philosophy bracing, and my curiosity about her as person and as writer stoked. I knew right then that I wanted to study her. Before I knew it, I had convinced the program panel for a scholarly conference to let me try to connect Robinson’s thought – Christian, compassionate, learned, science-loving, mystical, reasonable – with what I know of the teachings of Baha’u’llah on justice, individual spirituality, global consciousness, and the harmony of science and religion when both are rightly understood.

I’m not ready. (Not that the conference’s success rides on my brief discussion.) Robinson’s Absence of Mind is an awesome series of lectures she gave on the religion/science question, tough but rewarding reads that I’ll do again, as I am with her 2012 When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays on everything from a re-examination of the relationship between Judaism and Christianity, to an indictment of the current American cultural climate, to a hymn of Olympian praise to reading and libraries. (And LOTS more.) And her 2015 collection The Givenness of Things? Let me just give a few of the one-word essay titles (there are 17): “Humanism”, “Decline”, “Memory”, “Limitation”, “Realism”. She troubles herself not at all with small talk!³ She reminds me of Margaret Atwood, in the sense that she is a deeply literate and serious person, and a brilliant and well-read mind, and yet can make me laugh out loud (or groan) with an especially withering takedown of foolishness or hubris. (Robinson is an understated assassin in confronting the “parascientific thought” of the so-called New Atheists, Richard Dawkins and his co-religionists, for example.)

³ I won’t even get to the book she has called her most important: Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution (1989). Not this summer, anyway. It’s not easy to find, but from what I understand, it will join Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities on my top non-fiction shelf as a scathing and enduring criticism of social policy and governmental clumsiness. No doubt, it’s beautifully written condemnation.

To put it otherwise: I have written 1500 words on Robinson here, and not only does this not begin to express my admiration for her and an appreciation for what I’m learning, but it’s hardly getting me prepped at all for Montreal one week from now, for putting her life and career in the context of an emerging global consciousness! So wish me luck, gang. And read you some Robinson…

Update: Why don’t I insist on more days like this? I spent five or six hours reading, re-reading, thinking and writing a little about MR today (Monday 8 August). Doin’ it again tomorrow. My mind felt so used.

Good luck. I think I’ll take a look.

Robinson is on my reading list. Recommended by an old friend, a woman living in St. Jerome working as a brewmaster. Enjoy Montreal.