Steve Nash isn’t dying. He’s fantastically fit, a young man of 40 who would have his best years of productivity and accomplishment ahead of him if he wasn’t a professional athlete.

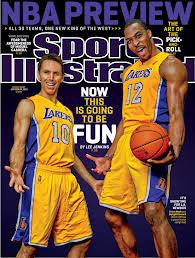

In the NBA, of course, he is a dinosaur, and a tiny one at that (at 6’3”, such is relativity), and no amount of his considerable brainpower or his incredible competitive drive is making a damned bit of difference. Less than two years removed from a Sports Illustrated cover – shared with Dwight Howard, the two newest Lakers! – the former point guard maestro is pretty much forgotten, except for Laker fans who snipe bitterly about his injuries, his team-hampering salary and his “selfishness”. At his uselessness, and worse. He’s played twelve games this cursed season, out of 72.

Grantland editor and Fan-in-Chief, Bill Simmons, had been talking book possibilities with Nash for awhile, but the man’s still playing (well, occasionally; actually, not much at all, but he’s still a Laker). He’s still a colleague, a peer, and he quickly realized he couldn’t write it the way he wanted, and wouldn’t be interested in doing so if it ignored all of his best insights. Besides, he is not only a certifiable Canadian sports hero without skates, but he’s already produced and/or directed documentaries and will continue to do so after his retirement from the hardwood. His own agonizing grind toward the end of his basketball career, he thought, might make a pretty good film, something that hasn’t been done before; Simmons agreed, but convinced him to do it in three short installments, and to do it NOW, in vivo, a Portrait of the Athlete as an Old Man, a peek behind the curtain of a sporting hero’s struggle to prove that I can still do it!

All three short videos have come out now, along with an introductory essay from

Well, you can palm that head, 12, but you can’t have it. It’s too much like gossip, but I’d love Nash’s take on playing with Howard, hinted at here.

Simmons, and they’re of interest for anyone who loves pro sport and would like to know more about one of the unusual men who’s been able to do it, and the rare specimen who reaches the peak of his sport. (I know, no championship rings, so yeah, he’s no Derek Fisher. Never mind Fisher, who has been a respectable player on some great teams; Nash pales, for some jewellery-addled idiots, before the brightness of such basketball giants as Dickie Simpkins, Sasha Vujacic, and Earl Cureton, all with multiple rings. Will Perdue was on board for four.) Two MVP trophies and, as Simmons mentioned in a recent podcast, being among the most “critically acclaimed” athletes of his time – these are pinnacles of the game. The Finish Line is riveting viewing for anyone who has particularly loved Steve Nash’s career, or who spends even the most occasional moments thinking about this bizarre socio-cultural phenomenon, a relatively recent one, in which among the most respected, even exalted, and financially rewarding careers is that of a professional ball-bouncer.

I think about this stuff all the time: I wanted to be one of those guys, and was never good enough, yet in middle age sports still have a hold on my heart and head that I struggle to explain, even to myself. Heck, my retirement after a few years of competitive, provincial-level fast-pitch softball with the Mount Hope Athletics had me grieving for months. (My fastball life still passes before my eyes. Sheesh. ) Detachment is hard. (There’s a book in there somewhere. I swear I’ll find it someday.)

So how does a guy like Nash leave it all behind? How does anybody? In these short docs, he has no real answers, but the confusion and the pain – and, absolutely, the denial, and the incredible efforts he makes to subdue his body and topple Uncle Time – are achingly obvious. We are right there with him, and it’s an uncomfortable thing to watch, and it’s supposed to be. It gets as close as most of these “inside story” books or films do to letting us know partial answers to the question we all have: what is Star X really like? Or in this case, how does it feel to be you, Steve Nash?

So I couldn’t help but think of Morrie Schwartz. Remember? Hot-shot, in-demand, superstar sports columnist Mitch Albom, in 1995, accidentally discovered that his beloved “Coach”, his mentor, a treasured college prof – someone he’d promised to stay in touch with, and in a busy life of doing/going/winning, didn’t – was dying. He was fading away with ALS, still called Lou Gehrig’s (and not Morrie Schwartz’s) Disease, and Albom had no time to lose. Through luck and desperation and a renewed and ever-growing love for his long-lost coach, the rat-racing writer carved out time for him in Morrie’s dying days. Tuesdays, in fact. You may have heard of Tuesdays With Morrie. I’m re-reading it now, and sharing it with a small class of Chinese undergrads going abroad for Master’s study; maybe this book will convince them that reading in English doesn’t have to be a brain-draining, weary slog. Anyway, here’s Mitch:

Morrie’s doctors guessed he had two years left.

Morrie knew it was less.

But my old professor had made a profound decision, one he began to construct the day he came out of the doctor’s office with a sword hanging over his head. Do I wither up and disappear, or do I make the best of my time left? he had asked himself.

He would not wither. He would not be ashamed of dying.

Instead, he would make death his final project, the center point of his days. Since everyone was going to die, he could be of great value, right? He could be research. A human textbook. Study me in my slow and patient demise. Watch what happens to me. Learn with me.

Morrie would walk that final bridge between life and death, and narrate the trip…

Mitch Albom, famously, walked some of that final way with his old teacher, cared for him, learned from the deeply humane, funny and wise words of Morrie Schwartz, and determined to do what writers do – get the story down – and what a surrogate son must – publish a book whose no-doubt-limited proceeds might help Morrie’s wife pay for his care. Who knew that a sports scribbler’s memoir of an old man’s agonizing death would be such a hit? Some hard-core sports types and other professional cynics lament the (incredibly popular) turn of Mitch Albom towards sentiment and spirituality – The Five People You Meet in Heaven, et al. – but Tuesdays With Morrie hits me, on second reading, with a heart punch and an insistent memory-jog: Time is short. Life is sweet. Better get after it. Love is the thing.

This brings us back to Steve Nash at The Finish Line. Again, he’s not dying, though leaving

“If everybody worked as hard as me, I wouldn’t be in the league,” said Nash at his MVP peak. Someday soon, hard work won’t matter. What’s next, “old man”?

a game to which you’ve given everything shouldn’t be dismissed as trivial. It must feel like a part of him is withering, every damned day except for a few; on the first day of spring, he bloomed briefly, with 11 assists in 19 minutes in a loss to the Washington Wiz. “Can’t sleep. Felt so good to play ball,” he tweeted, and then didn’t play for a week. That has to hurt. He got 15 minutes and six dimes in a 142-107 mauling by Minnesota Friday night. So, was there joy? Did it feel good to be out there that blow-out night? How far can the “love of the game” – and I have no doubt he loves it desperately – take a man? I don’t like to think of The Great Steven as a KGDC guy, as Jalen Rose would put: keep gettin’ dem checks, Steve! But then, nobody’s ever offered me millions to be on their team, either.