Not everybody gets Don DeLillo. If you don’t pay attention to the contemporary art of the novel, you may not have even heard of him. Presto! That’s why I’m here today! Mr. D. is in the pantheon of current American fiction writers. Literary fiction, that is – this is not a “page-turner”, and he’s no Dan Brown. (That would be like comparing Vincent Van Gogh to the guy who makes the blue outlines for the old “paint by numbers” craft sets.) And I’m no DeLillo expert: of his major, and often hefty, acclaimed novels – White Noise, Mao II, and the famous Underworld – I have read precisely none. I tiptoed into his work with a comparatively slender novel called The Body Artist. It was clever, admirable stuff, a bit morose, and I don’t remember much about it. It left me cold, or maybe I was there to begin with. I may, however, need to read it again.

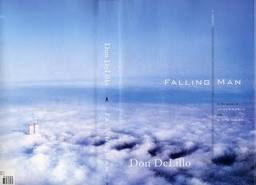

My recent second voyage into DeLillo Country was his 2007 novel Falling Man, the post-9-11 book he hadn’t intended to write. I found it on a remainder shelf in a mega-bookstore back home in Canada, next to a non-fiction book by Martin Amis in the same historical vein: The Second Plane. I was trawling for all-things-I-can’t-get-in-China, and not only were these two volumes a few cultural steps higher than the Harvey’s burgers and Baskin-Robbins cones I’d been gorging myself on last July, they also seemed fated together to increase my lugging for the next month’s return trip to China. And here’s why The Body Artist might deserve a second look: Falling Man is a novel I’ll be thinking about for a long time, one that I immediately started re-reading once I’d finished. How did he do that? It’s brilliant, but also an accessible introduction to a challenging writer.

We later find that one of the central characters is Keith Neudecker, a thirty-something lawyer and lover of games. We first meet him, though, as he staggers down a New York street. The novel opens like this:

“It was not a street anymore but a world, a time and space of falling ash and near night. He was walking north through rubble and mud and there were people running past holding towels to their faces or jackets over their heads. They had handkerchiefs pressed to their mouths. They had shoes in their hands, a woman with a shoe in each hand, running past him. They ran and fell, some of them, confused and ungainly, with debris coming down around them, and there were people taking shelter under cars.

“The roar was still in the air, the buckling rumble of the fall. This was the world now. Smoke and ash came rolling down streets and turning corners, busting around corners, seismic tides of smoke, with office paper flashing past, standard sheets with cutting edge, skimming, whipping past, otherworldly things in the morning pall.

“He wore a suit and carried a briefcase. There was glass in his hair and face, marbled bolls of blood and light….Things inside were distant and still, where he was supposed to be…”

He is one of those vivid, deathly people we remember, covered in dust and by copious amounts of somebody’s blood. The briefcase is not his own. He has made the long walk down from high in the North Tower of the World Trade Centre, and he doesn’t know where he’s going until a friendly plumber, just after the tower collapses, offers him a ride. He shows up at the apartment door of his wife and son, from whom he has been estranged for nearly two years. Now what?

It is Lianne Glenn, his wife, who visibly suffers the deepest trauma “after the planes”, as DeLillo repeats like a Greek chorus. She watches to see whether Keith will stay. She watches and reads stories of terrorism obsessively. A highly educated free-lance editor, Lianne is spooked and livid about the woman downstairs who plays the vaguely Islamic music day and night. She can neither sleep nor watch her seven-year old son innocently slumber. Her house is haunted.

Who is the falling man? There are several candidates: a performance artist, those desperate souls seen diving (or blasted) from the towers’ windows, Keith’s poker-playing friends – “shallow people leading giddy lives” – Keith himself, Lianne’s suicidal father, maybe the human race. What happens after the stunning opening scene? Life does, or something like it. “These are days after,” DeLillo writes. “Everything now is measured by after.” He measures the external circumstances and inner conversations of interesting people after tragedy, all imagined in astounding and incredibly ordinary detail. (Even the pre-impact life, and the clumsy attempts at philosophy, of one young jihadist are shown, in three short interludes that follow each of the novel’s three parts.)

That haunting, terrible photo. It looms over the book, though it is never shown and barely mentioned.

Part One is titled after a mysterious Mr. Lawton. “Three days after the planes,” Lianne reflects on the eight years of “extended grimness called their marriage”, aided by her arch and curious mother, a scholar who’d never approved of her marriage to this hockey-loving, poker-playing man. Keith finesses his way past barricades to get to this apartment near the Towers, but comes away with nothing but a few scraps of mail. Lianne gets back to her volunteer work with dementia patients, men and women whom she encourages to write and remember for as long as they can. By ten days after the planes, both are curious about “the kid”, and the secret childish speculations that Justin carries on with neighbour kids (and a pair of binoculars). Lianne becomes morbidly curious about her mother’s European lover and his mysterious past. Keith finally looks at the briefcase he carried out of the North Tower, and makes a diffident attempt to learn of its owner. He is most dedicated, it sometimes seems, to the post-operative exercises he does to strengthen the wrist that was the only lasting physical injury he’d sustained on September 11.

“Keith…was going slow, easing inward. He used to want to fly out of self-awareness, day and night, a body in raw motion. Now he finds himself drifting into spells of reflection, thinking not in clear units, hard and linked, but only absorbing what comes, drawing things out of time and memory….Or he stands and looks….Something is always happening, even on the quietest days and deep into night, if you stand a while and look.”

Lianne grows angrier, and no amount of obsessive reading and attempts at Islamophilic understanding make any difference for her. It is only through her outraged reaction to Keith’s disconcerting detachment that we first learn of friends he’d lost, that day of the planes. Yet, despite this, and the dismaying knowledge of what the kid and his little friends were looking for, Part One ends with Keith’s statement, a mainly hopeful one, that “we’re ready to sink into our little lives.” He seems okay with that, and so does Lianne.

The second part of the novel, again titled with the name of a character we never quite meet, is more of the same seemingly mundane scenarios and adjustments, yet there is always an undercurrent of (mostly) muted terror. DeLillo is a cool observer, but his language is rich, sometimes poetic, and his eye incredibly keen. Examples abound: Keith’s use of the word “actually” in a casual mention of the briefcase brings their separation vividly back to Lianne. Her mother’s lover, to challenge her bitter denial of terrorist grievance, sits “hunched and peering, leaning toward her now. ‘First they kill you, then you try to understand them. Maybe, eventually, you’ll learn their names. But they have to kill you first.’” Keith is joined by Justin (“the kid”) as he watches a televised card game: “He watched without interest. It wasn’t poker, it was television….Lianne came in and sat on the floor, watching her son. He was seated at a radical slant, barely in contact with the chair and staring helplessly into the glow, a victim of alien abduction.” We see Keith and his buddy Rumsey, a small shadow that occasionally darkens the novel, loving their midnight hockey, “following the puck across the ice, body crashing the boards, free of aberrant need for a couple of happy shattering hours”. (This is merely among the best formulations ever of the joyful gravity that sport has for men.) A fly marches across a ceiling as one lonely pair has an essential conversation below. An airborne terrorist fastens his seatbelt before impact. (Knocked me out and sideways, that detail did. Imagine!) Small observations like this accrue, off-handed yet relentless, forming a picture of real people trying to live real and damaged lives, and not incidentally an image slowly develops of the nations, of the civilizations in which they live. I think this is what DeLillo does.

Lianne, fearing obsessively but “wanting to be safe in the world”, nevertheless periodically attacks others in surprising ways, whether her mother for her passive acceptance (so like Lianne’s own) of the mysteries wrapped up in the murky life of her lover, or her scary verbal stabbing of her son’s little friend. Eventually, although she often walks the streets timidly, nailed to the cross of obsessive remembering and visualizing, Lianne takes one startlingly violent and clearly dangerous action. Keith follows suit in the mattress department at Macy’s, in a macho collision that could have been hilarious if it hadn’t happened so suddenly or been shown so naked of the erotic colouring our culture so often associates with violence. Like real violence, it was shocking. Part two ends, “thirty-six days after the planes”.

The third part, in a now-familiar way, is titled with an unfamiliar man’s name. (Hey, maybe this is THE Falling Man. And this time, it is. One of them, anyway.) It is three years after the planes, and people march against America’s vengeful (et cetera) wars in western Asia. Lianne still works to remember, Keith to forget, and both are less than successful. Has their little family survived? Yes and no and maybe so. “Just people sharing the air,” Lianne ventures. She loses close relations, while Keith regains one laconic but important one in a surprising yet inevitable way. The kid gets older, and throws a baseball harder and harder. Their lives go on, and DeLillo shows us what it’s like to be them, to think the thoughts that they do and watch them deal with memory and loss in their peculiar and familiar ways. Then the novel ends. Almost.

DeLillo does this, too. He manages to circle back, at the novel’s end, to the planes, to the now-beardless young jihadist, who does not doubt in his Book (except when he does), who is sure (mostly) that it is good to “carry your soul in your hand [and] to forget the world…to be unmindful of the thing called the world”. One more time, in a brilliant yet simply-written turn, DeLillo shocks the reader, this time into considering resentful terrorists and privileged Americans together, in the most

blazingly violent event all of us have ever seen (over and over). Their stories merge in the same darkly burning, unforeseen high-speed wreck of a single sentence. The minutes and hours before we found Keith Neudecker on the street are filled in, and we find ourselves back on September 11. We understand, just a little better, as we peer inside the North Tower, just after the planes.

The rewards for the committed reader are great, though he writes at the peak of the old writing teeter-totter, “show, don’t tell”. There’s work to be done for the reader, and sometimes we feel suspended high in the air, unsure of what is happening despite our perfect view. The author never abandons us, never jumps off the seesaw, and if we look at the novel with the same calm, clear-eyed attention that he brought to the writing, the rewards are great. This is a somber, marvellous book that Don DeLillo has written, but you will actually have to turn the pages yourself.

Nice review. We experienced this book similarly, though I was already well-indoctrinated into DD’s world when I read this one. That fight in Macy’s was tremendous, an amazing literary depiction of violence.