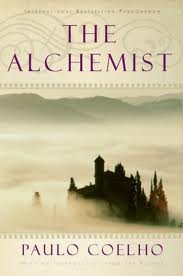

There was a year, back there somewhere in the early oughts, when it seemed everybody was reading Paulo Coelho’s short novel, The Alchemist. First published in Portuguese in a small late 1980s print run, it became first a Brazilian and then an international literary phenomenon. More copies were sold than live in my country (my home country Canada, that is, not China!). Perhaps it was the contrarian in me, maybe it was just a case of distraction, or it is conceivable that something in the breathless reaction some people were apparently having (and the frenzy with which it was bought) that put me off it. Sometimes ignorance and bias aren’t all bad.

I should’ve liked it. It is a story that speaks unabashedly of spirit, of living simply, of pursuing extraordinary dreams, and while I’m no great exemplar of them, I can enthusiastically get with these ideas. With The Alchemist, though, I was impatient with the constant and repetitive internal monologues of the first-person narrator central character, a young shepherd named Santiago. (My first of several oh-oh, this smells borrowed moments came with his name, reminding me immediately of Hemingway’s solitary protagonist in The Old Man and the Sea. Early on, my grumpy unofficial subtitle to Coelho’s book became The Young Man and the Sheep. Actually, though, it’s more likely a nod to the famous Camino de Santiago, a walking pilgrimage in Spain. Still, ideas borrowed from many places crop up repeatedly, and sometimes it felt a bit like an anthology of rented notions.) I was even less patient with the dialectical, expository conversations about the meaning of life that he has with a rotating cast of cardboard characters, including the desert, a rather petulant Wind, and the sun. I wanted some story. I wanted a little more credit for being able to tease out meaning, rather than having it served to me on a platter.

The story. Santiago roams languidly, idyllically through rural Spain, in the company of sheep. He wants to see the world. He dreams of Egyptian treasure in an abandoned church. He meets King Melchizidek, Old Testament mentor of Abraham. (We’re not sure how.) He meets a Gypsy fortune teller. (She seems more real, but it’s hard to tell.) He meets and instantly longs for two young women, the first his Rosaline, the second an unusually patient Saharan Juliet. He meets a 200-year-old alchemist in an oasis. From each, he learns of the Soul of the Universe. He meets with war, famine, desertion, beatings, apathy, mockery and a book-loving Brit on a camel. None of them seem like real people or genuine situations. His last meeting is a violent one, which ends with magnificent unlikelihood: the leader of the attackers, just in passing, a song before I go, relates the dream he had had while in that place, which tells Santiago exactly what he needed to know. I understand that this is not gritty, realistic fiction, but it felt clumsy to me.

The meaning. Each person has a special destiny. Follow your heart. Watch for omens. Act on them. What your heart desires, the universe unites to help you find it. Become acquainted with the Soul of the World. I am, generally, supportive of spiritual searching, and The Alchemist seems to be full of it, yet its collection of Sufi, Christian, Muslim, alchemical, poetical — William Blake’s idea of seeing “the world in a grain of sand” makes an uncredited appearance, for example, but maybe I’m being pedantic — Arab and New Age philosophy seemed not only derivative, but without much of a story to carry it. Santiago is guided by magical emissaries of wisdom, but the wisdom felt like vague statements of what many modern folk want from their spirituality: an affirmation that pursuit of your personal desires is The Right Thing to Do. And for all its gauzy conversations about soul and heavenly aims, the protagonist (attention: avoid the end of this paragraph for its possible Spoiler Alert!) gets a surprisingly material set of rewards for his two years of desert wandering.

I’ll admit I started looking for “omens” in my own life, the kind of clues that Santiago becomes convinced are there as guides for all of us, and I can see why the book became popular. It’s brief, but it gives the feeling of seriousness; it’s an easy read, but offers a sweetened dose of existential encouragement to live boldly, if a little selfishly. It’s a little like faith, but without all that annoying responsibility and sacrifice. If you like your spirituality in small doses, and reading that won’t require much of you but a few hours, you might enjoy The Alchemist a lot more than I did. Coelho himself, not long before writing the book, completed the legendary Spanish pilgrimage to the burial site of the Christian Saint James, which gave his protagonist a name. This, his first novel and second book, certainly touched a vivid nerve and has made its spectacular way in the world because of its hearty appeal. We want spirit. We need to remember the inner journey. I think Mr. Coelho made it a tad too easy, but tens of millions worldwide disagree.

[Many of these “Better Read Than Never” reviews appear — always more briefly — in an English/Chinese magazine in my city. It’s mainly for expatriates and those who like to hang with ’em, and it’s called Focus on Dalian. This one will be immortalized in glossy print by mid-October.]