[9-minute read]

Just down there, in the He Said/She Said section of this here site, is the latest quotation that got me to thinkin‘…

The citation is from James Naismith, in 1892, weeks or months after he scribbled down the 13 Rules of the game he had just invented. He was far too humble to call it “The Naismith Game” or anything like it, so he called it “Basket-Ball” “because there’s a [peach] basket and a ball, so…” I saw a reference in something I’d read to what might have been the second thing he wrote about his new baby, this sport he’d been asked to design in order to give young Christian men — it was invented at the YMCA’s International Training Centre, after all — a way to keep in shape during a Massachusetts winter. (And this, from a Canadian! Perhaps there was no ice rink at the Springfield YMCA? Maybe he held an anti-hockey grudge? Or — horrors! — he didn’t know how to skate?) Anyway, this was the reference, a copy of which hangs in the Naismith Museum:

“THE PHYSICAL AND MENTAL REQUIREMENTS OF BASKET-BALL”

“Agility, accuracy, alertness, cooperation, initiative, skill, reflex judgment, speed, self-sacrifice,

self-confidence, self-control and sportsmanship.”

There are 12 qualities that he wanted the game’s disciples to know and strive for. And I couldn’t help noticing how close they come to alphabetical order! (So yes, I’ve given Coach Naismith a little editorial help in what follows.) In the interests of obsession and whimsy, let’s think of them not only in this (improved) order but also with my (mainly) approving comments on Dr. Naismith’s “requirements” after each one:

ACCURACY. When modern hoopswise guys talk about “athletic ability” and the physical prowess of prospects and pros, they routinely ignore this one. They favour sprinters, long-armed discus-throwing types, jumpers and other track’n’field demonstrations of “athleticism”. Even 128 years later, we need to be reminded that hand-eye coordination, the ability to make that leather globe go through an elevated fruit bucket (or between flailing limbs to an open teammate) is fairly important, too. Cooz. Earl the Pearl. Nash. Steph. KD. Luka. Accuracy.

AGILITY. The ‘80s-era NBA marketing campaign was a video debate: Quickness! STRENGTH! It was mainly a big-man, little-man argument over which was more essential to basketball. (And specimens like Jordan, Olajuwon, Barkley and James have them both, in plenty.) I’ve always been a Quickness Guy, though I realize what a phony dichotomy it is. Powerful slow dudes don’t last, especially in the modern NBA, and spaghetti-armed rabbits tend to get skinned pretty quickly. I like Naismith’s insistence on ‘agility’, but modern coaches don’t talk about it much. (Football guys do.) But agility implies balance; it does little good to be quick if you can’t stop or change direction “on a dime”, as we said back when a 10-cent piece had some value. And ‘agile’ is such a great adjective!

ALERTNESS. Here’s another old-school term, one that the Coaching Wizard would have admired and did use. Heads-up. Vigilant. Reading the game. Relentlessly seeking even the smallest of advantages. High school kids don’t do this much, so in 2020 I’ll still be coaxing my boys to notice, more often, how much time is left on the clock, and what the score is, who has the best chance to score for us, and the most dangerous of our opponents. Alertness starts there. Players hypnotized by the ball on defence, or who study the their defender’s shoes when they receive the ball, get an F in Old Man Naismith’s class.

COOPERATION. “Play hard, play smart, play together”. Dean Smith might’ve been first with that, and a myriad coaches use it as mantra. There are lots of contrary currents in society in general, in sports, and in basketball especially: individualism: the “player empowerment” that is surely preferable to their being professional pawns but which has lessened the value of “team”; and, the fetish for that most Uncooperative of skills, showtime dribbling. Oh, what I’d give for a few boys that could actually PASS THE BALL. Or value team spirit. (I can feel the pitying or dismissive glances out there, even typing that hoary old phrase.) Or understand that loyalty is its own reward, not to mention that building true teams can’t, even in 2020, be done by throwing together a bunch of people in free-agent auctions, or recruiting blitzes using the coolest gear. With a salute to Robert Fulghum, All I need to know about basketball I learned in kindergarten.

INITIATIVE. Naismith conceived the game as free-flowing and reactive. He didn’t imagine the overcoaching that was to come, the positional specialization; I guess that he only dimly realized how his game would, at its highest levels, come to greatly favour the freakishly tall. But the best coaches have always understood that players need to be trained to make decisions on the fly; it ain’t football, and we run the “no-huddle offence” all the time. (Wooden: “The team that makes the most mistakes will win.” Contrarian, in part, but also recognizes that alert players are useless without the encouragement to act on what they see.) Of course, initiative needs to be balanced not only by skill but by the willingness to not try everything, or to try the same damned thing every time.

REFLEX JUDGMENT. I love this one, mostly because it’s as far from cliché as we can get – I’ve never seen this phrase outside this list. Quick hands, quick feet, quick mind. This requires alertness, initiative, AND skill, plus the “hands like wild birds” that John Updike speaks of in his poem “Ex-Basketball Player”: His hands are fine and nervous on the lug wrench / It makes no difference to the lug wrench, though. (Ouch. Outside a surgery theatre or a painter’s palette, those sensitive hands are rather wasted away from the court, but such is life.) And some players just have that feel, the timing that allows them to act or react in ways unteachable and uncopiable. (See: Bird, Larry. Johnson, Earvin.)

SELF-CONFIDENCE. The old riddle: does sport reliably nurture this quality, or merely reveal it? It’s never fully formed in a young athlete, and certainly requires fertilization and encouragement from somewhere. On the other hand, it’s also constantly fragile in some kids, and well-nigh inextinguishable in others. But if repetition is the mother of skill, then self-confidence is at least skill’s stepchild. We think we can do a thing because we’ve done it, or something like it, before. Those of us that coach cling to the belief that self-confidence is a biproduct of sporting involvement, and we may at times be right. It certainly is essential to athletic performance, especially when the stakes are high.

SELF-CONTROL. Among the many things that the superstar Kawhi Leonard is celebrated and admired for, aside from his genetic gifts and his hard work, don’t sleep on his eerie self-control. He demonstrates this physically, in terms of his patience and willpower in getting to exactly the place he needs to be on offence and on ‘D’. But mentally, dare I say spiritually, he seems never to get ahead of himself; never to distract himself with the peripheral aspects of his work (he’s absent from social media, it appears); never to over-estimate the value of a single play, or a win, or a loss; and rarely to betray even the slightest hint of frustration or any form of emotional imbalance. It has to spook his opponents just as it amazes and strengthens his teammates. Naismith would’ve loved him: never too hyped and agitated, never obviously down on himself or his teammates.

SELF-SACRIFICE. Here’s an unpopular bid for nomination among contemporary virtues! Certainly it was no stretch for a dedicated Christian teacher like Naismith to consider this central to his new game; he would have regarded self-sacrifice as essential to any human activity or community. Mastery over the insistent self remains a chief characteristic of maturity – the ability to delay gratification, to consider others before ourselves, to put events into perspective. Choosing a collective good (say, winning or team unity) over an individual one (“gettin’ buckets” or personal credit) is basic to team sports, especially the nine-man game that Naismith originally conceived. It’s always been a challenge for kids to embrace this, and it’s only getting tougher.

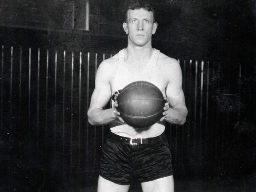

Here’s Coach Wooden in humble victory. He was also the young baller in B&W up above. (AP Photo, File)

SKILL. Here is yet another counter to the coachly compulsion for measurables. It matters little how wide the wingspan or how high the hops if players can’t execute the offensive and defensive footwork and at least the basics of the ballhandling magic that are at the foundation of the game at its best. This is most obvious with respect to *shooting* and, once again, passing (everybody can whip the ball between his legs nine times while eight other players stand around, but who practises *passing*?), but also applies to skills good players have when they’re without the ball. While I’m ranting, another pet peeve: all the ways in which the world’s greatest players have the most leeway to travel. Quickness! STRENGTH! SLOPPY AND CYNICAL MANIPULATION OF THE RULES! Anyway, Coach Wooden put ‘SKILL’ at the centre of his famous Pyramid of Success. Coaching is *teaching*, not just grabbing the biggest and fastest. ‘Nuff said!

SPEED. Speed. “There is more to life than increasing its speed,” said Gandhi, but then he wasn’t a ball coach. The distinction from agility – or quickness, especially laterally – is key. The fastest player at my high school is not the most agile or balanced, and his changes of direction don’t match his pace, but when he’s out in the open floor, with or without the ball, it’s scary/great. SPEED THRILLS. LeBron’s sheer velocity is still incredible, though he doesn’t run quite like he used to. Giannis, sheesh. Jason Kidd. But we all know about the racehorse kid (or pro) who just doesn’t seem to know when or where to go, or hasn’t the skill or alertness or initiative or agility or reflex judgment to outrace the opponent instead of himself and his teammates. Or maybe he just can’t bloody SHOOT. (In contrast, who had all the other qualities in such profusion that his modest sprinting ability didn’t prevent him from playing the game at a blinding pace.) Still, Naismith was right about the power of speed, and not just on the fastbreak. Chasedown blocks à la LeBron are awe-inspiring, but so are balls tipped away from behind, or a player who runs her guts out to stop an attacking player, or create a front-court trap, when it looked like an opposition layup. Speed changes the game, never more so than now, where even Ottawa high schools play the 24-second clock, “pace and space” is king, and the game has turned outside-in. And I *adore* a fast-paced practice.

SPORTSMANSHIP: I’ve never heard Kawhi’s steely calm referred to as ‘sportsmanship’, but then that’s another apparently stale-dated concept. Now maybe I haven’t seen enough of Mr. Leonard, but it occurs to me that he also doesn’t flop or embellish contact to try and trick the officials, which would likely have been, for Naismith, a clear sign of a ‘poor sport’. The man has had one technical foul in his entire career. Somewhere along the line, the ideal of sportsmanship was discredited, especially in team sports; especially in North America, it seems too often we hear only the second word in “respectful winner” and “gracious loser”. Respect the coach. Respect the opponent. Respect the officials. Respect the game. (Spell it out, Aretha!)

Yup, for James Naismith these were the Twelve Disciples of his fresh-out-of-the-box game in 1892, and we could do a lot worse than dwelling on them — as coaches, parents, players, even as fans — a little more, and maybe a little less on dunk compilations and highlight mixtapes. Just sayin’, don’t get all mad.

Well-played, Dr. Naismith!

Thanks for your insights. It was enjoyable to read and I look forward to integrating some of your thoughts moving forward.

Take care.

Nice. Basketball virtues 👍

Thanks for the simple, yet meaningful, reminders of what this game is all about. I think that we, as coaches, do our best with many of these items but the good ones touch them all!

Thanks for the nourishing food for thought. Naismith was definitely into something: keep it simple.