[3-minute read]

Blogs are personal, but as I think about how to begin this quick review – these things always seem to start with Me – I’m fazed by my self-centredness as a writer. Ergo, as a human, I suppose. Look how interesting I am! is what I hear now. Aren’t I clever? (Hurt. Hilarious. Lonely. Sensitive. Tough. Damaged. Special. Not Like Them. Better Than You. Worse Than You Know.) Ugh. But blogs are personal…

I had done my duty to the fine young pair who showed up for Thursday’s SuperCool Chance to Play Basketball On the Freshly Varnished Hardwood Before School Even Starts! (Little O and Uncle Drew did great.) I had even been a good little writer afterward, though I confess that I cheated the typing gods by shortening the time. (Still, though, my thinking was interesting – take it from me – and I may have found a way out of a large, thorny maze where my book got lost.) Cezanne et Moi seemed tailor-made as a writer’s treat and re-treat, and it was the last screening at my cinema of choice. So yeah, I rewarded myself with a luscious dessert when I hadn’t actually finished my first course, but the guilt faded fast. I’m glad I went.

Irrational confidence alert: through BioPic Magic, I feel that I now understood 19th-century painter Paul Cezanne without much effort, and intimately know his lifelong friend and sometime antagonist, the writer Emile Zola, without having read a single novel of his. (But that’s what Wikipedia is for, right? Um, right?) I am hungry to know these two artists better, though, and was exposed to a nearly two-hour, loving meditation on friendship, love, and on the meaning and practice of the creative life. WIN. I’d gladly watch it again.

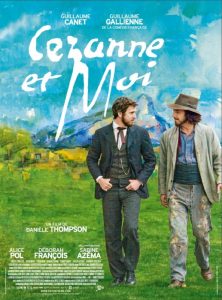

It’s a gorgeous film to look at. Scenes toggle from the brightness and glory of the French countryside, especially Cezanne’s beloved Aix-en-Provence with its red-rock hills, to the dark Parisian intimacy of Zola’s impoverished youth and, eventually, the antique splendour of his eventual fame and wealth. Renoir and Manet, de Maupassant and Monet, among many other great names of the astounding arts scene of mid-19th century Paris, populate the social scenery of the film, but it is dominated by the Two Guillaumes, Canet (Zola) and Gallienne (Cezanne), who play the artists from their early 20s to early old age. Gallienne¹ is less convincing as the ever-impetuous youth than as the uncompromising, difficult wild-man artist of the film’s end; the opposite is true for Canet’s Zola, who fares better as the shyly observing, wide-eyed young man than as the aging lord of the literary manor. Still, both performances are very fine, as is that of Alice Pol as Gabrielle/Alexandrine, Cezanne’s youthful amoureuse and Zola’s steadfast wife. (These two men were extremely devoted but often horribly bad friends.)

¹ Guillaume Canet is a well-known French movie actor and sometime heart-throb. Gallienne is primarily a theatrical performer, meanwhile, and I was intrigued to note that on the C et M poster and in the film’s credits, he is referred to grandly as “Guillaume Gallienne de la Comédie française”. That’s a mighty theatrical tradition at work; I don’t think there’s an equivalent in English-language drama.

I was taken in. True, I went with that very intention: I watched writer/director Daniele Thompson’s oeuvre on two makers whose names ring on over a century later. I inhaled their obsession. I noted their habits. I got to be the voyeur, gazing at other artists’ impressions of Paul Cezanne and Emile Zola as they work, doubt, create, falter, love, hate, dream, succeed and work. (Both were phenomenally productive, driven, inspired, though apparently with radically different ways of channelling their personal wars of art.²) My own youthful furies having roared along decidedly non-artistic routes, it is always both a source of regret – I wish I’d found an earlier access road to writing, and hiked it more – and inspiration – look at ‘em GO! – to immerse myself into the lives of creative folk. It’s stirs me up, even when I am only rubbing cinematic shoulders with the Great Makers.

² Where credit is due: I love and re-read Steven Pressfield’s War of Art, and am gathering like-minded lunatics in September to study and get my arse kicked by it.

Cezanne et Moi is an energetic, lush film. The inevitable reviewer’s blurb for the film biography of a painter – “great subject, too small a canvas” – has been applied to Thompson’s movie. Maybe there’s some truth there. While it’s not surprising that someone with more knowledge of these artists might feel irritated or short-changed by it, I found it a superb dessert treat: fine, rich ingredients were lovingly and thoughtfully prepared, and I savoured them slowly. I can still taste it, and a second helping sounds good to me.