In Canada, we have (steadily more meagre and occasionally even contemptuous) government-funded radio. Alarmists – unlike the always-judicious, ever-moderate me – might call the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation an endangered species. Last Chance to Hear! Broadcasters, Artists and Thinkers in Their Natural Habitat! It’s a pretty pale safari, but I’m on it. The CBC’s a national treasure.

Yesterday I listened to Q, Radio One’s flagship weekday arts ‘n’ culture show. It’s hosted by a grandson of Rwanda, a Canadian-as-socially-conscious-rap MC known as Shad. (By night, he’s a bouncy, smiling hip-hop groove-ster with a real band. By day, he talks to Salman Rushdie and Margaret Atwood and Darryl McDaniels, the DMC in rap/rockstar band Run DMC. In between, he’s Shadrach Kabango.) Actually, I was re-listening to an extended podcast recording of a conversation I’d heard part of earlier in the week. (I think I was sweeping. Or washing dishes?)

They were talking dystopias, especially regarding Rushdie’s new novel Two Years, Eight Months, and Twenty-Eight Nights. It’s full of malevolent genies, time travel, a corruption-exposing baby and a whole lot of thinly-disguised Now. It’s also apparently very funny, as Rushdie is no permanent pessimist and wanted to explore the “strangenesses” of our time with some inventive and comic strangeness of his own. He wasn’t trying to outgrim Margaret Atwood, in other words. (Though it must be said that her MaddAddam trilogy is nastily, wryly funny if you can suspend despairing recognition, at least for a moment.)

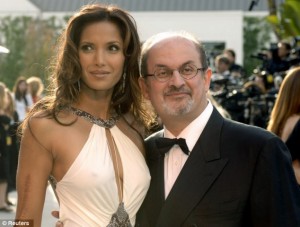

This was only the first (and then second) time I’d heard Rushdie interviewed, surprisingly, and I found him an engaging and generous interviewee. Shad didn’t even need to finish his questions, sometimes, which must have felt, oh, efficient, certainly, and maybe even flattering. (I can’t help but wonder if the four women from whom he is divorced might take a different view. The man does seem accustomed to being listened to.) It was superb radio, about half an hour of smart talk without a commercial – or any sort of – interruption.

Towards the end, Shad asked a poignant, maybe even beseeching, question. I think he was hoping for a ‘No, certainly not!’, but it didn’t come. So, asked the brainy and hip-hoppity young host, are we a civilization in decline? Rushdie’s answer, though he acknowledged that it may be a “boring and kind of grandfatherly thing to say”, was a gentle but definite ‘YES.’ I was instantly reminded of the title and contents of a favourite read, John Ralston Saul’s The Unconscious Civilization. Rushdie paused, verbally hemmed a little, and then quietly said,

“We have lost a kind of seriousness….

There’s something important about engaging with ideas and having a strong ethical conversation in a society [about] what kind of society it wants to be…”

We have lost a kind of seriousness. As softly, as regretfully as Rushdie put it, that phrase echoed for days in the catacombs of my mind, bouncing off Saul, vibrating in sympathy with the writings of Shoghi Effendi, and recalling Neil Postman’s best-known book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, too.¹ Rushdie is optimistic, not only maritally but in the global perspective, believing that we will find a way – like a teenager pulling an all-nighter to get an essay done – at the last moment to pull ourselves away from the brink of imminent disaster, of which he sees plentiful evidence, climatic and otherwise.

¹ Do check this link. I don’t know how something from 1985 could be so charmingly fusty — after all, I was alive in those days! — but as old-fashioned as it seems, and as retro as Postman’s hair might look, the man’s warnings often even seem stronger and more relevant in 2015.

I agree with him. It makes no sense to me to believe anything other. Still and ever and on and on, wouldn’t it be great if we could reduce the price of our unconsciousness by engaging the world less trivially, by acting less carelessly, and by thinking less distractedly? To generally behave as if there was something more to life – mine, yours, ours – than purchased pleasure and store-bought enthusiasms? (And reality TV? And fantasy football leagues? And Baconators?)

Salman Rushdie (b. 1947) was born and raised in Mumbai, India, but has mainly lived in England and America since his university days. His second novel, Midnight’s Children, won the great Booker Prize, and later both the 25th – and 40th –anniversary citations as the “Booker of Bookers”. You may have heard of The Satanic Verses, which brought against him a death warrant issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini (may he wriggle in discomfort). I especially loved his youth novel Haroun and the Sea of Stories. He is brilliant and inventive, humane and thoughtfully concerned, though I probably wouldn’t go to him for marital advice.

The opening paragraph of Shoghi Effendi’s The Promised Day Is Come (1941). [Editor’s NOTE: A stunning thing, this paragraph. Shoghi Effendi was neither quiet nor diffident in his assessment of his century. Thanks, Mr. D.]

“A tempest, unprecedented in its violence, unpredictable in its course, catastrophic in its immediate effects, unimaginably glorious in its ultimate consequences, is at present sweeping the face of the earth. Its driving power is remorselessly gaining in range and momentum. Its cleansing force, however much undetected, is increasing with every passing day. Humanity, gripped in the clutches of its devastating power, is smitten by the evidences of its resistless fury. It can neither perceive its origin, nor probe its significance, nor discern its outcome. Bewildered, agonized and helpless, it watches this great and mighty wind of God invading the remotest and fairest regions of the earth, rocking its foundations, deranging its equilibrium, sundering its nations, disrupting the homes of its peoples, wasting its cities, driving into exile its kings, pulling down its bulwarks, uprooting its institutions, dimming its light, and harrowing up the souls of its inhabitants.”

I regret to advise that his warnings penned after WW2 are even more harrowing.

Paul