For a football running back, one of the greatest and most electrifying to watch, what could be better than having the initials “TD”? When I first started paying attention to

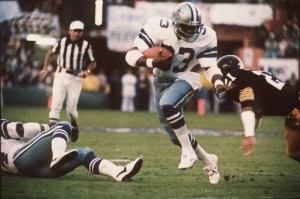

Tony Dorsett, he was a skinny freshman tailback for the University of Pittsburgh Panthers. Skinny, yes, but also shocking in the ease of his changes of pace and direction, all that effortless speed and the instinct to elude. He made defenders disappear.

Yes, but only sometimes. You don’t win Heisman Trophies as the best in American college football, and you don’t churn through a Hall of Fame career in the brutal territory of the National Football League, without massive numbers of massive collisions with massive, furiously destructive opponents. Now, Touchdown Tony is a 59-year-old husband and father whose family sometimes hasn’t known what to make of him. He has been moody, sometimes upbeat but too often morose or scarily angry, and he tells of one day being unable to remember the way to take his young daughters to a practice he’d chauffeured for many a time. He tells of dark thoughts, but doesn’t want anyone to think he’ll hurt himself any more than his chosen profession already has.

He went looking for answers. The doctors at UCLA figured it out, but what does he do with this knowledge? Although a conclusive diagnosis, as I understand it, can’t be made until the brain is sectioned and stained and microscopically examined – that is, post-mortem – Dorsett now believes that he has Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a physical degradation of the brain that results from repeated violent head-knocking. You may have heard of CTE, as more and more cautionary tales emerge from the ranks of (especially) retired hockey and football combatants. The most alarming, sobering ones come with the examinations of the brains of depressed, mentally chaotic men, several of whom had killed themselves. Seau. Probert. Duerson. Boogaard. And the first to be diagnosed with CTE, Pittsburgh Steeler “Iron” Mike Webster, demented and in pain post-career and dead by 50, though — or because? — he’d been one of the finest and toughest players ever to give up his body for the NFL.

The list is growing, and the questions about what violent gaming does to men aren’t just about crippled knees and shrieking shoulders anymore. Former hockey great (current writing great) Ken Dryden recently wrote about the cruel, bipolar question now being asked of Tony Dorsett, and of Mark Duper and Bernie Kosar and the many other men who entertained us with their willingness to run and jump, hit or be hit, in what are not truly

“contact” sports but collision sports. (Investigators liken long football careers to volunteering to be a passenger in thousands of car accidents.) So, knowing what you know now, would you do it again? As Dryden writes, it’s a question whose likely answer – I would, I loved the game — is the NFL’s, and the NHL’s, only real defence: they chose to do this. The opposite answer requires a pro player to disavow large parts of his own life, and to reject an occupation that gave him his best friends, his self-image, his lifestyle, and his (however uncertain) standing in the world. Not easy, and it begs another question.

What about non-pros? What about me?

I’m 56. I’ve been a teacher, a coach, a writer. I never even made a varsity athletic team in university. (I chose to try out for basketball over a better bet, football, because I wanted to have knees when I was 40; we weren’t even thinking about what happens to a footballer’s brain.) However, I’ve had two major, lights-out, night-in-hospital concussions in my amateur sports career: one as a high school sophomore football player, one as a thirty-something fast-pitch softball nut. I remember the moments before contact, but there’s over an hour in each case that’s been erased from the record. Hmm. There was also that bad-hop baseball to the ear at shortstop (bells were ringing), getting run over picking a bad throw at first base (my first car accident, grade 8), four years of high school football in bad helmets, one actual car accident that stunned me awhile, and sundry knocks on the head in gyms and on grass, here and there.

I’m taking inventory, because my life is a blessedly fortunate one by all the standard metrics. Yet I am sometimes overwhelmed by rip-tidal frustrations that come from dealing with a typically stubborn, domestically rebellious teen who does his homework, though inefficiently, spends too much time on his laptop, and sometimes takes a disrespectful tone. (Such are his crimes.) In the last six months, I’ve had three or four volcanic fits of loud-mouthed pique over foul calls in pick-up basketball. (Did I mention that I’m 56?) How can these things take me by surprise? This is my fourth son, after all. I’ve played at much higher levels than Chinese pick-up in three sports, coached one for over 20 high-intensity years, and though I was pretty fiery, I nearly never had such blowouts. They take me over. I’m worried. I have plans for this brain. (This family, these young men, these relationships.) Oh, and while I’m taking stock, there was that (likely accidental) elbow smash to the eyebrow on a baseline drive to the basket last February. The other guys in the gym were worried about the blood, but I wondered what that industrial noise in my head might mean for my temporal lobes. Shit. Maybe my cage has been rattled once too many. Or twice. Or.

Before he spent four years offering himself as wily prey for college linebackers to crush, before his twelve years running for his life in the NFL, where ball-carrying careers average

abut three seasons, Tony Dorsett had already been knocked cold and out of action by eleventh grade, and maybe not for the first time. He’s now the latest poster boy for a growing examination of the safety, the morality, of spectator sports whose fan-avatars collide with each other with ever-increasing force and consequences. Where are we going with this, more and more commentators ask. At age 59, Dorsett now asks himself the same question, in conference with his family and his own addled skull. His grace, power and speed are long gone, but they wouldn’t help anyway.

Where am I going with this, I wonder. I write about it. I try not to think about it. I run about it. (I run away from it.) I do things to help my body be a good home for my mind, but I can’t help worrying that I’m going to lose it. (Again.)